No products in the cart.

November 3, 2025 10:55 am

November 3, 2025 10:55 am

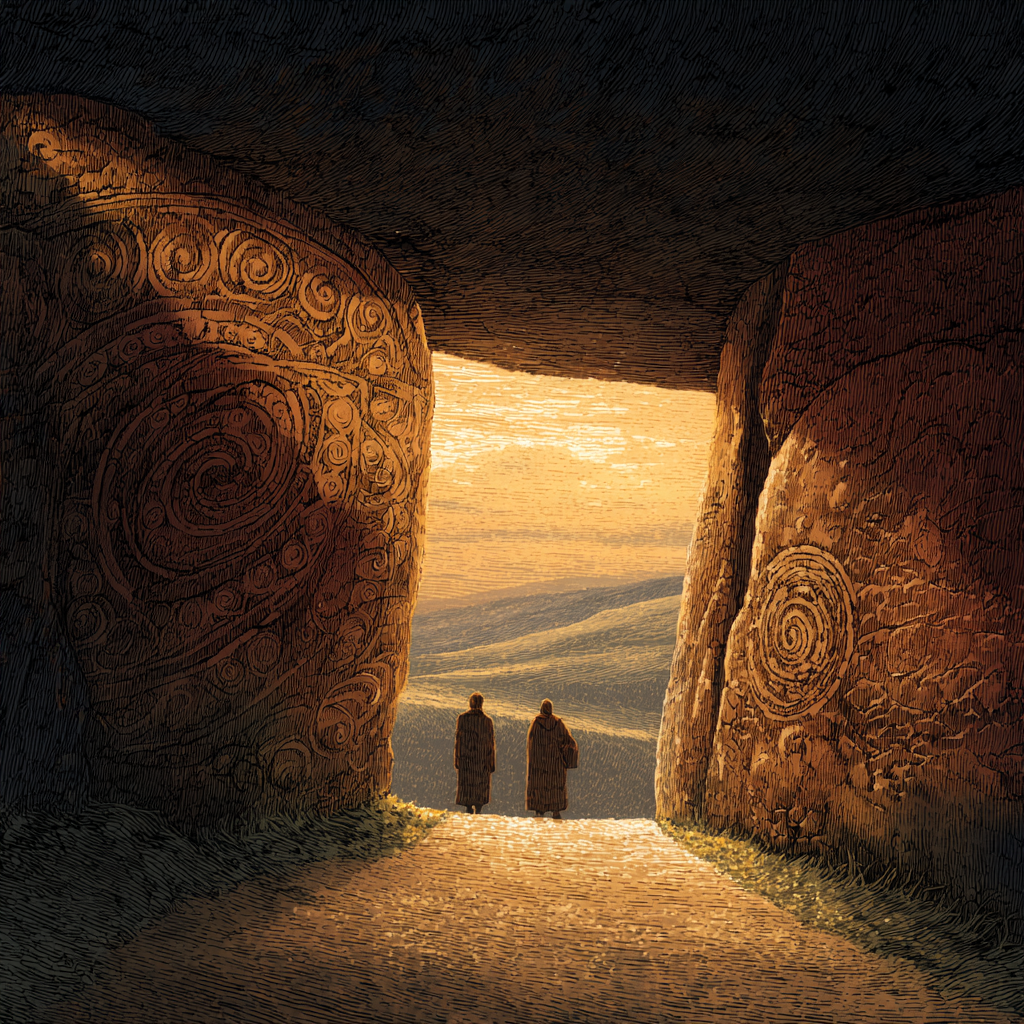

Every winter solstice celebration carries echoes of ancient ritual and survival. The winter solstice, the shortest day of the year, has been observed across Europe as a threshold between darkness and renewal.

From the flicker of the hearth fire in Celtic cottages to the roaring bonfires of northern villages, ethnographic and archaeological research reveals how people marked this moment as both an ending and a beginning.

Drawing solely from verified academic studies, this article explores the symbolic, ritual, and agricultural meanings of the winter solstice in Indo-European and northern traditions.

Christina Hole’s Winter Bonfires (1960) remains one of the most complete ethnographic accounts of midwinter fire customs in the British Isles.

Hole observed that communities gathered around flames during the shortest day and longest night of the year, performing rites that reached back to early pagan times.

In Scotland, Ireland, and Wales, villagers lit need-fires, leapt through flames, and scattered ashes on the soil to bless the fields for the coming year (Hole, 1960, pp. 218–221).

By tracing these bonfires through Guy Fawkes Night and New Year fires, Hole demonstrated that the winter solstice celebration never disappeared but evolved.

The symbolic burning of old wood represented both purification and fertility, embodying the human need to celebrate the return of the sun’s warmth.

Her documentation of the Burghead Burning of the Clavie and the Lerwick Up Helly-Aa festival shows how such midwinter ceremonies preserve communal identity while acknowledging cosmic order (pp. 223–227).

Through these findings, fire emerges as the essential metaphor of the solstice. It is both practical light and sacred symbol, linking agrarian hope to celestial rhythm.

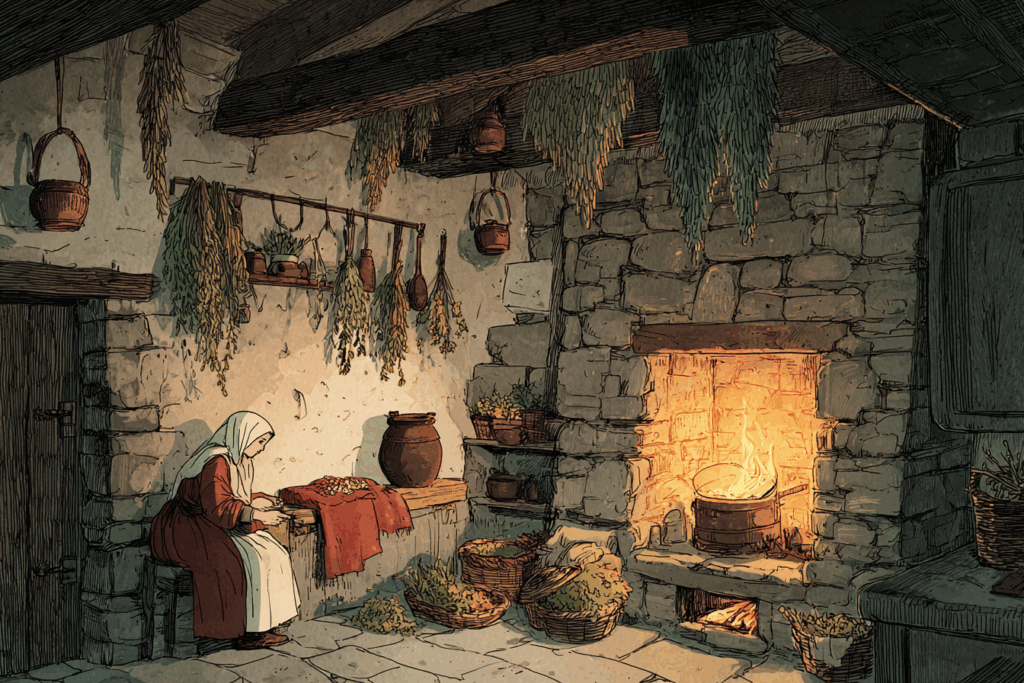

Séamas Ó Catháin’s (1992) research into Irish hearth traditions reveals a quieter but equally significant dimension of the winter solstice: the domestic altar of flame.

On Brigit’s Eve, households tended the hearth fire as if it were a living being.

Families laid out a bed for Brigit, offered food, and whispered protective charms while the coals glowed through the night of the year (Ó Catháin, 1992, pp. 12–14).

The hearth, according to Ó Catháin, symbolized the sun within the home.

Its constant warmth represented continuity amid the darkest night, uniting spiritual and agricultural fertility.

Reading ashes for omens and carrying embers between houses created networks of shared blessing (pp. 15–16).

The practice also mirrored Brigit’s association with wells and springs, connecting fire and water as twin sources of renewal.

Through these rites, families in the northern hemisphere maintained a sacred household rhythm that paralleled the wider solstice traditions of communal bonfires.

The domestic yule log became a microcosm of cosmic fire, an intimate way to celebrate winter solstice through prayer and daily care.

Geraldine Spare (1986) offered a psychological reading of Celtic seasonal thought that illuminates why the winter solstice carried deep spiritual resonance.

In her Reflections on Winter, she described the Celtic world as one that “measured time by nights rather than by days,” suggesting an instinctive comfort with darkness (Spare, 1986, p. 29).

This acceptance transformed the longest night of the year from an enemy into a teacher. Rather than opposing light and dark, Celtic spirituality viewed them as mutually sustaining.

The solstice thus became a meditation on stillness and a moment to pause within the cycle of death and rebirth.

Spare interpreted this seasonal introspection through Jungian psychology, equating it with the reconciliation of opposites within the self (pp. 32–33).

The Celtic way to celebrate was therefore reflective rather than defiant.

While northern neighbors lit great fires, Celtic poets and mystics preserved inner flame through storytelling and ritual silence, both serving the same purpose: to encourage the sun and honor life’s cyclical balance.

Earl R. Anderson’s (1997) linguistic study of Old English texts shows how the solstice structured Anglo-Saxon understanding of time itself.

Early English culture recognized only two main seasons, winter and summer, and each defined by a solstice (Anderson, 1997, pp. 231–233).

The day of the winter solstice marked both the conclusion of the agrarian year and the promise of renewal.

In literature such as The Wanderer and Deor, winter symbolized hardship, endurance, and moral testing. Summerrepresented generosity and divine favor (pp. 237–239).

Anderson traced these linguistic and poetic patterns back to Proto-Germanic roots, where winter likely meant “wet season,” linking it to fertility and the stored vitality of the earth.

His research clarifies why winter solstice marks more than the start of winter. It is the axis of transformation, a reminder that every frost conceals potential.

The solstice was not simply an astronomical date but the pulse of survival in northern life.

Terje Oestigaard’s (2025) archaeological and ethnographic chapter connects midwinter to the deeper Indo-European symbolism of water and fertility.

In Scandinavia’s Bronze and Iron Ages, farmers performed rituals at frozen wells and springs during the December solstice, honoring the hidden flow beneath the ice (Oestigaard, 2025, pp. 144–146).

These “foaming wells,” which never froze, represented life persisting in apparent death. Farmers poured beer or milk into them, offering nourishment to the earth while symbolically awakening its sleeping forces (pp. 147–149).

The winter solstice celebration thus embodied the same principle as the yule log: preserving life through symbolic action.

Oestigaard’s analysis of horse and cattle rituals, such as watering livestock at sacred springs on December 26, reinforces how northern peoples perceived midwinter as a sacred negotiation between humans and nature (pp. 148–150).

The return of the sun depended on maintaining this ecological balance.

These findings link directly to Ó Catháin’s hearth-fire cults and Hole’s communal bonfires.

Across the northern hemisphere, the elements of fire and water worked together to sustain both land and spirit.

Albert B. Costa’s (1977) short essay The Sun compiles reflections on the solar cycle from scientific and mythological viewpoints.

He noted that every solstice carried dual meaning: an astronomical phenomenon and a metaphor for mortality and renewal.

In summarizing Isaac Asimov’s The Flaming God, Costa highlighted how nearly every civilization identified the sun as a divine being whose apparent death in winter and resurrection in spring inspired religious myth (Costa, 1977, p. 260).

His references to Roman Saturnalia and the Mithraic feast of Sol Invictus show how the December solstice became embedded in Mediterranean theology of the rebirth of the sun.

When Christianity later placed its nativity feast near the shortest day, it continued rather than erased that cosmic symbolism.

Costa’s synthesis provides the broader solar framework within which all northern solstice celebrations can be understood.

Returning to Hole’s ethnographic evidence, the bonfires of winter were more than seasonal amusements.

They were tools of social cohesion and agricultural blessing. Hole observed that ashes from communal fires were scattered over ploughed fields to invite fertility (Hole, 1960, pp. 221–222).

These ashes represented the transformation of matter through fire and a visible metaphor for the rebirth that the solstice promised.

She noted that even after the rise of Christianity, such fires persisted because they met essential human needs for warmth, light, and unity.

Each winter solstice celebration reaffirmed the community’s collective resilience. When the sun risesafter the darkest night, those flames reflect shared endurance rather than mere spectacle.

Across these sources, a repeating mythic pattern emerges. Ó Catháin’s Brigit embodies sacred domestic fire, while Oestigaard’s Scandinavian kingship rituals such as the sacrifice of King Domaldi to restore fertility and to translate that same principle into political theology (Oestigaard, 2025, pp. 142–143).

Both link the preservation of life to ritual renewal through symbolic death.

Geraldine Spare’s (1986) reflections align psychologically with this structure. The solstice becomes a liminal state where transformation occurs through acceptance of darkness.

Together, these studies reveal a shared Indo-European and Celtic understanding of cosmic reciprocity: life requires the offering of energy back to nature, whether as flame, water, or consciousness.

Although these sources describe pre-modern communities, their insights remain strikingly relevant. The winter solstice continues to serve as a moment to pause, a seasonal reminder of humanity’s fragile relationship with nature.

Oestigaard’s ecological interpretation of Scandinavia, Anderson’s linguistic reconstruction of Old English winter, and Spare’s spiritual psychology all converge on a single truth.

The winter solstice celebration endures because it reflects a universal rhythm: descent into stillness, then return of the light.

As Costa’s analysis reminds us, even the most modern observer of the sunrise at Stonehenge participates in an ancient dialogue between science and sacred time.

To celebrate the solstice is to recognize continuity across millennia.

Together, these studies show that the winter solstice was never a single festival but a constellation of meanings uniting fire, water, fertility, and faith.

Each tradition, from the hearth to the hilltop bonfire, expresses the same ancient understanding: that through darkness, the world is renewed.

Anderson, E. R. (1997). The seasons of the year in Old English. Anglo-Saxon England, 26, 231–263. Cambridge University Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44510523

Costa, A. B. (1977, March). The sun. Journal of College Science Teaching, 6(4), 260. Taylor & Francis, Ltd. https://www.jstor.org/stable/42988019

Hole, C. (1960, December). Winter bonfires. Folklore, 71(4), 217–227. Taylor & Francis, Ltd. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1258110

Ó Catháin, S. (1992). Hearth-prayers and other traditions of Brigit: Celtic goddess and holy woman. The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, 122, 12–34. Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25509020

Oestigaard, T. (2025). Farming, fertility and foaming water: Indo-European ritualizations of life-giving growth forces in Scandinavian agriculture. In J. H. Larsson, T. Olander, & A. R. Jørgensen (Eds.), Indo-European ecologies: Cattle and milk – Snakes and water (pp. 133–161). Stockholm University Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/jj.32247978.10

Spare, G. (1986, Winter). The Celtic tradition: Reflections on winter and the Celtic spiritual attitude. The San Francisco Jung Institute Library Journal, 6(2), 26–33. Taylor & Francis, Ltd. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/jung.1.1986.6.2.26