No products in the cart.

June 12, 2025 7:37 am

June 12, 2025 7:37 am

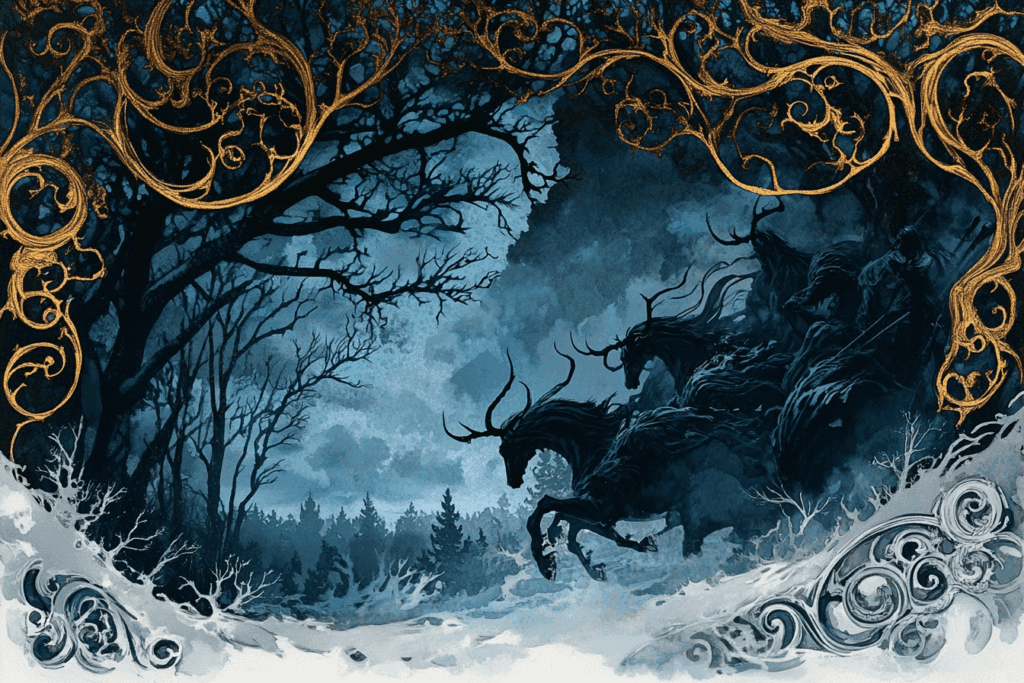

The wild hunt is one of the most enduring and eerie motifs in European folklore.

It’s a spectral procession of ghostly riders galloping through stormy skies, forest paths, or the borderlands between the living and the dead.

Known by various names across the Germanic lands, the wild hunt is a mythic symbol that transcends time, manifesting both in medieval chronicles and modern pagan revival.

Its roots run deep in norse mythology, but its branches stretch across centuries of folklore, legend, and ritual.

In this post, we explore the Wild Hunt’s origins, symbolism, regional expressions, and the ancient gods said to lead it .

In Norse mythology it is most notably Odin, the Norse god of death, war, and the wind.

The wild hunt is often associated with winter and particularly the season of yule.

It is a kind of haunted hunting party, usually composed of the dead, spectral hounds, and supernatural riders led by a fearsome leader.

This leader of the hunt could be a god, a dead king, or a folkloric hero.

There are many names such as Odin, Woden, Herne the Hunter, King Arthur, or even Frau Holle, depending on the region and period.

As M.M. Banks, a well known academic folklorist and mythologist, noted in her seminal 1944 essay The Wild Hunt, the phenomenon was interpreted as having pre-Christian roots, perhaps originating in ancestral cults or beliefs about the souls of the dead.

Banks emphasized how the wild hunt appears in various names and forms across Europe, but always bearing a core resemblance: a hunting party in full cry, storming across the skies, often foretelling doom or sweeping up the souls of the dead.

The wild hunt was thought to be a nocturnal flight linked to the belief in a soul double appearing in animal form, heard rather than seen.

Monks heard them sounding and winding their horns in the middle ages.

According to Banks, hearing the hunt was often considered an omen, while seeing the wild hunt meant death or madness.

The appearance of the wild hunt could portend plague, war, or famine.

In this sense, the wild hunt is one of those legends that blurs the line between folklore and cosmic dread.

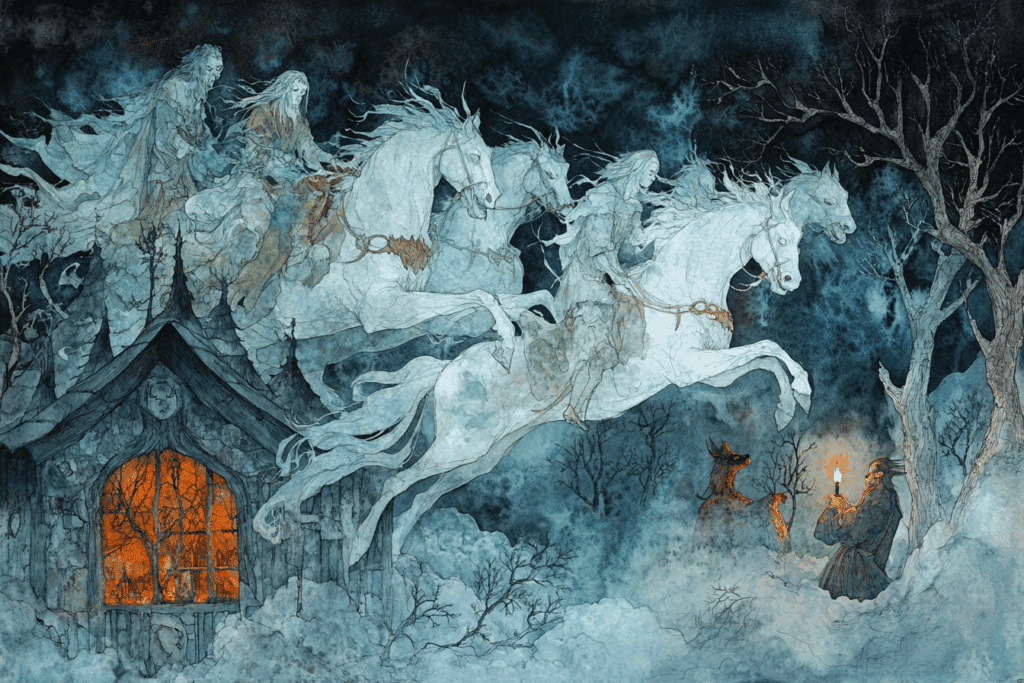

In Norse mythology and religion, the god Odin is the most prominent figure said to lead the wild hunt.

As the god of the dead, god of the wind, and god of the slain, Odin’s role as the leader of the hunt is symbolically rich.

The norse myths portray Odin as a wanderer and seeker of knowledge, but also a terrifying figure.

He rides the eight-legged steed Sleipnir, commands the dead warriors of Valhalla, and speaks in riddles and prophecies.

Odin’s hunt was heard storming through the air during yule, the midwinter period when the veil between worlds thins.

According to medieval sources and later folklore, the wild hunt of Odin rode with a ghostly procession of warriors, hounds, and valkyries .

Indeed, the wild hunt is said to abduct lost souls or sweep them into the underworld in order to assist them through the process of rebirth (in German language, these souls were called ‘Heimchen’).

This belief persisted in early modern periods. Jacob Grimm, philologist and author of Teutonic Mythology, called the wild hunt “Woden’s Hunt,” and interpreted the wild hunt phenomenon as having deep roots in germanic beliefs about the god odin.

Grimm noted that the hunt could sometimes include women, children, or the recently dead which is a symbolic sweeping up of souls in transition.

While the figure of Odin as the archetypal leader of the Wild Hunt dominates Norse mythology, deeper academic inquiry, especially through the lens of historian Ronald Hutton who reveals that the so-called “Wild Hunt” is a modern scholarly construct synthesized from a spectrum of older, more diverse folkloric traditions.

Hutton critiques Jacob Grimm’s 19th-century Deutsche Mythologie as the point of convergence where disparate motifs—nocturnal ghostly processions, demonic hunters, and folk tales of the prematurely dead—were amalgamated under the label “Wild Hunt.”

Grimm, influenced by Romantic ideals, treated local peasant traditions as frozen relics of a pagan past, using modern folklore to fill the gaps in early medieval texts.

However, Hutton suggests this conflation may obscure rather than clarify the original meanings of these spectral traditions.

He outlines three distinct types of processions in early sources: the demonic punisher, the condemned mortal hunter, and the wildman pursuing spectral prey—each lacking the composite features of the later “Wild Hunt” archetype that Grimm popularized.

Ethnographically, the motif of the Wild Hunt spans an extraordinary geographical and cultural range.

Folklorist M. M. Banks noted that even in early 19th-century India, reports of spectral cavalry and echoes of hooves persisted in folk memory, reflecting how such motifs become embedded in collective consciousness regardless of origin.

Simultaneously, Lotte Motz, in her examination of the Alpine goddess Perchta and her entourage, documented how elements traditionally associated with the Wild Hunt.

There, phantom armies, frenzied music, spectral howls, and grotesque, fur-clad figures were observed in midwinter rites and condemned in Christian sermons as early as the ninth century.

These references underscore that the “wildness” of the hunt was not just symbolic but was performed, experienced, and feared.

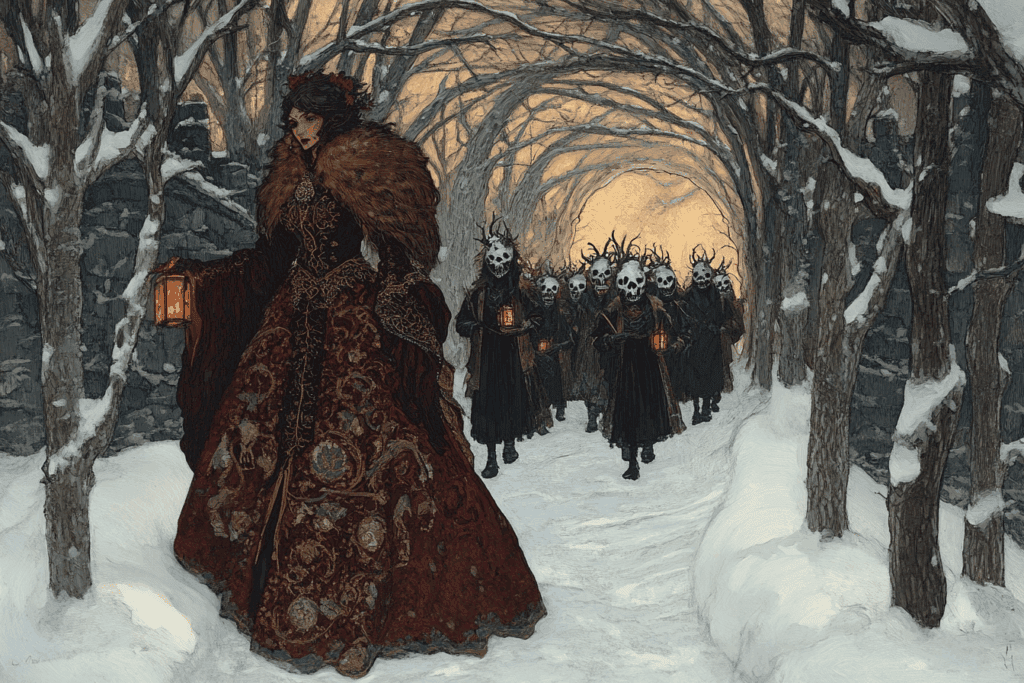

The idea of a female-led procession, often with humans claiming to participate in spirit form, persisted especially in southern Germanic and Alpine traditions, suggesting regional variants long before their retroactive standardization in mythological scholarship.

The association between yule and the wild hunt is ancient and recurring. In northern European folklore, Yule is not just a time of festivity but a liminal period when spirits walk and the dead ride.

The wild hunt goes forth during this time, often with Odin at its helm, or in some versions, with female leaders like Perchta or Holda.

Lotte Motz, historian of myth and ritual, explores these figures in her 1984 paper The Winter Goddess: Percht, Holda, and Related Figures.

Motz notes that female figures often led the hunt in Alpine traditions, and that this was not a contradiction but a complement to Odin’s role.

The wild hunt’s various names across Germanic and Norse traditions reflect this dual gender symbolism.

This is widespread from Woden’s Hunt in England to Perchta’s Hunt with her Husband Berchthold in Bavaria and the Swabian region of southern Germany.

The idea of the wild hunt as a sign of divine presence or punishment was used to explain strange weather, ghostly noises, or disappearances.

Tales of the wild hunt were told to children to discourage disobedience, and in folk beliefs about the god Odin, the hunt became a mythic symbol of cosmic renewal, balance and transformation.

In the ethnographic records collected by folklorists like Karl Simrock and Wolfgang Menzel, we find localized stories of the wild hunt embedded in regional Germanic traditions.

German scholar Simrock describes the wild hunt as a symbolic reflection of battle, death, and the harvest cycle.

Much of their ethnographic and comparative mythological research has never been published or translated before into English.

The hunt is led by a god or hero — sometimes Odin, sometimes an anonymous ghostly rider — who pursues lost souls or punishes the wicked.

The German philologist Karl Simrock emphasized the distinctly Old Norse character of the Wild Hunt, focusing particularly on the role of Wotan (Odin) as both god of the dead and storm deity.

In Handbuch der deutschen Mythologie, Simrock draws upon regional folklore across German-speaking Europe, particularly Saxony and Lower Germany, where Odin is said to ride with ghostly followers through the storm-filled winter skies.

This nocturnal procession, known variously as the Wilde Jagd or Das Wütende Heer, often accompanied by howling winds and spectral hounds, served as both an omen and moral enforcer.

Simrock connects the sound of howling winter winds with Odin’s ride, and emphasizes the use of magical charms by peasants to ward off the god’s host or seek prophetic dreams through the visitation of the god in sleep (Simrock, 1855, pp. 229–230).

These elements reveal a syncretism between pagan religious practices and post-Christian folklore, where the wild hunt becomes a liminal myth between the living and the dead, fate and punishment, and memory and fear.

The German scholar and folklorist Wolfgang Menzel, in Die vorchristliche Unsterblichkeitstslehre (1837), offers another angle: the wild hunt as a kind of ancestral reenactment.

He notes the haunting trope of a black horse with no rider which is a mount for a soul taken by the hunt.

He also describes how Freyja, the norse goddess of death and fertility, sometimes appears as the leader of a female wild hunt.

These spectral huntresses ride through the air, seeking justice, vengeance, or lost men.

According to these sources, wild hunt legends were not static.

Versions of the myth evolved through the middle ages and into the early modern era, blending pagan motifs with Christian fears.

Sometimes the hunt is described as a divine punishment, other times as an otherworldly parade of the souls of the dead.

Menzel identifies a cosmological duality in Germanic myth: Odin leads male warriors into Valhalla, while female deities like Holle, Perchta, or Freyja guide the souls of women and children.

This gendered bifurcation in the afterlife, he argues, is a defining feature of pre-Christian Norse-Germanic religion.

German scholar Menzel points out that the Wild Hunt, whether under Wotan or Perchta, functioned as a “midwinter renewal ritual,” appearing around Yule to collect or punish souls, especially those unburied or morally impure, but also to assist the souls of unborn ancestors to come up and to go through a process of rebirth (Menzel, 1870, pp. 165–168).

In these local traditions, the ghostly procession was more than myth: it was believed to haunt real places, appear in the sky, or ride invisible roads.

Such beliefs situate the Wild Hunt not just in mythology, but in lived folk religion as a spectral drama enacted between worlds, preserving echoes of ancient Norse cosmology well into early modernity.

And even today this can be experienced each year particularly in Switzerland (e.g. Silvesterklausen), Austria and the Bavarian and Swabian-speaking regions of southern Germany (Krampuslauf, Perchtenlauf, Buttnmandl, Klausentreiben), where Winter Masquerades reenact this myth.

The wild hunt has never vanished. In popular cultures and modern subcultures it lives on in local ghost stories, Christmas-time warnings, and pagan holidays.

In the pagan religion of Wicca, the wild hunt is reinterpreted as a mystical rite of passage, marking the death of the old year and the birth of the new.

In modern fantasy and literature, from Tolkien to The Witcher, the wild hunt is often portrayed as a ghostly army. Indeed, it is terrifying, majestic, and bound to destiny.

The wild hunt in modern culture reflects a deep yearning to reconnect with ancestral memory and myth.

Ronald Hutton, British historian and expert in paganism, explores this continuity in his 2014 study The Wild Hunt and the Witches.

Hutton argues that the wild hunt is one of the few myths to survive both the Christian suppression of pagan religion and the rationalism of the Enlightenment.

It is a tale that refuses to die, a kind of a ghostly archetype that still gallops through the forest of collective imagination.

The wild hunt is one myth, but it has many faces.

The wild hunt motif has various names across Europe. It is most commonly found throughout the Germanic speaking Europe, as noted by the Italian historian Carlo Ginzburg (1991), but it appears in many localized variants.

Woden’s Hunt, Percht’s Ride, Herla’s Host, and the wild huntsman reveal its adaptability and longevity.

The members of the hunt change, the leader shifts, but the core image remains: a supernatural hunting party riding between worlds.

Some versions of the wild hunt depict Odin and his hounds. Others feature black horses, ghostly riders, and spectral horns echoing in the night.

Some say the hunt catches sinners, others say it brings blessings.

In all cases, it is a legend that speaks to the fear and awe that ancient peoples felt toward death, nature, and the unknown.

Today, seeing the wild hunt is rare but not impossible, according to some folk beliefs.

Those who witness it may be swept into its ranks, lost to the mortal world. Others may find protection in silence or ritual.

This could be a bell rung, a prayer whispered, a candle lit.

From old norse myth to early modern folklore, the legend of the wild hunt continues to haunt the cultural imagination.

Whether led by Odin, Freyja, or some unnamed ghostly general, the hunt remains a symbol of chaos, fate, and the unbreakable tie between the living and the dead.

In every horn blast and galloping hoofbeat, we hear the echo of a world where gods still ride, the dead still walk, and myth lives just beyond the threshold of the forest.

Academic References: