No products in the cart.

September 6, 2025 8:41 am

September 6, 2025 8:41 am

When readers today look up sidhe meaning, they often expect a straightforward sidhe definition: “the sidhe are fairies.”

Yet in truth the word has a deeper ancestry.

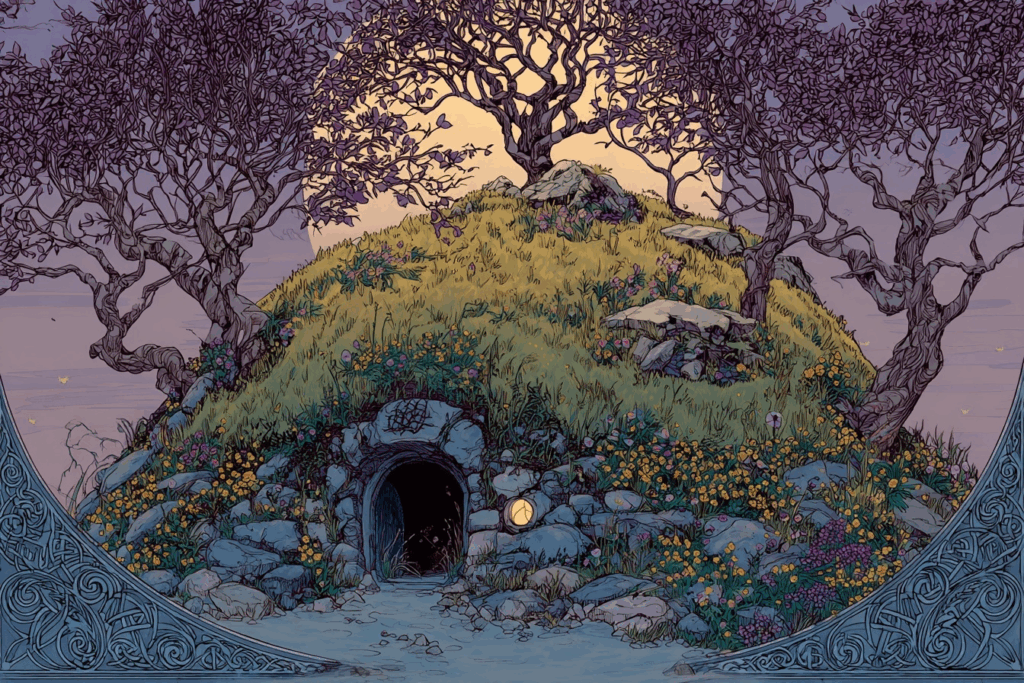

In Irish mythology, sídhe (pronounced “shee”) originally meant “a fairy hill or mound.”

These fairy mounds, beautiful grassy barrows that dotted the Irish landscape, were thought to be entrances into the Otherworld.

Over time, sidhe came to mean not just the mound, but the fairy folk who lived within it, the aos sí, or “people of the mounds.”

This duality explains why sidhe meaning is so hard to pin down.

Are the sidhe spirits of the dead, descendants of the Tuatha Dé Danann, or gods and goddesses reduced to faeries by Christian scribes?

Scholars of Celtic mythology and Irish folklore have debated this for more than a century.

To understand what sidhe means, we must turn to philology, folklore, and the literary imagination of Ireland, where every manuscript, ritual, and folk memory tells a part of the story.

In Old Irish, síd simply meant a hill or mound.

David MacRitchie’s Notes on the Word “Sidh” (1893, p. 368) emphasizes that the term applied to the tomb-like hills and the inhabitants who dwelled within.

The sidhe were thus both mounds and fairy people.

Medieval chroniclers explained that when the Milesians defeated the Tuatha, those earlier gods retreated into the hills, becoming the aos sidhe. From then on, a sidhe was both a mound and a deity-like inhabitant.

Comparisons exist across Europe.

Norse tales speak of haugbui (mound dwellers), while Scottish folklore recalls “hill-men.”

Gaelic sources, too, insist the sidhe are people of Ireland, not ghosts but powerful otherworldly beings.

The word shee, still used in modern Irish and Scottish English, preserves that sound.

The sidhe meaning, then, is never only about landforms: it is about a folk based belief that the earth itself concealed faerie dwellings.

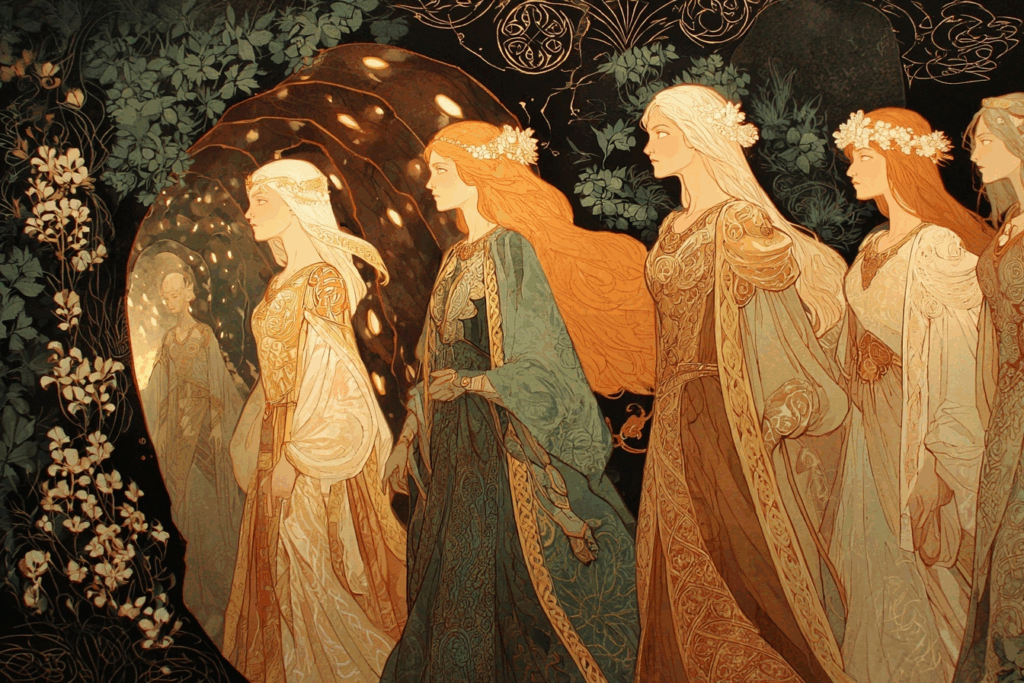

The sidhe were long associated with the Tuatha Dé Danann, the great gods and goddesses of Irish pagan lore.

After their defeat, they retreated underground, becoming inhabitants of the sidhe mounds.

In medieval manuscripts, they are often called the daoine-sidhe (“fairy people”), indeed, the luminous faeries who continued the ancestry of the old gods.

This explains why sidhe meaning cannot be divorced from pagan cosmology.

They were pre-Christian divinities, tied to danu, to Mac Lir, to the mystical tír na nóg (land of the dead).

Writers like W. Y. Evans-Wentz, in The Fairy Faith in Ireland, linked them to a broader fairy faith shared across Celtic lands.

In this view, the sidhe are the Tuatha Dé Danannremembered in diminished form, still ruling the realm beneath the hills.

Yet sidhe meaning also shades into the ancestry of the people themselves.

Many folk tales describe the sidhe as spirits of the departed, dwelling beneath sidhe mounds that were once tombs.

Here, the sidhe overlap with the souls of the dead, lingering in the land of the dead.

This ambiguity was not lost on Yeats.

As Kathleen Heininge explains, Yeats saw the sidhe as both immortal and soulless, faeries doomed at the Last Judgment but radiant in the meantime (2004, pp. 102–104).

Some traditions imagined them as fallen angels caught between a place in heaven and earth, others as the folk memory of gods turned into elf-like beings.

In this sense, sidhe definition stretches across categories: faerie, ancestor, spirit, witchcraft-tainted otherworldly beings.

In Irish folk tales, to meet the sidhe was dangerous.

Brides might be stolen by a fairy woman, infants replaced with changelings, strong youths taken into the Otherworld.

Time inside the sidhe ran differently: a night of dancing might equal a century outside.

Eating their food meant risking entrapment.

Still, the sidhe could bring gifts: music, poetry, and healing.

The fairy faith in Ireland taught that respect was essential: offerings at sidhe mounds, charms against the unseelie or seelie courts, rituals to guard against pookas and selkies.

As MacRitchie noted in Druids and Mound-Dwellers (1910, pp. 260–262), chronicles sometimes blamed Druids, sometimes sidhe, for the same magical acts.

The sidhe were feared but also revered — liminal fairy folk, tied to folk magic and Gaelic ritual.

By the nineteenth century, the sidhe had become central to Irish Fairy and Folk Tales collected by Thomas Crofton Croker, Patrick Kennedy, and Lady Wilde.

As Anne Markey notes, these collectors often reshaped the tales to fit Catholic or political values (2006, p. 32).

The sidhe were no longer just dangerous; they became part of a folk based Irish pagan school of identity.

W. B. Yeats elevated the sidhe into emblems of Ireland’s poetic soul. His Celtic Twilight portrayed them as creatures of “untiring joys and sorrows,” both alluring and tragic.

Yeats drew from the fairy faith, blending oral folk material with esoteric philosophy.

For him, sidhe meaning crystallized into paradox: they were faeries who were both the brilliance of Ireland and its sorrow.

So what does sidhe mean? The sidhe definition is layered:

Today, sidhe in Ireland is a word of many echoes: of faeries, elves, the sith of Scotland, the aes of Celtic gods, the daoine-sidhe remembered in Gaelic lore.

It reminds us that in Celtic mythology, the sidhe are not just fairies: they are the fairy people, the gods turned ancestors, the inhabitants of hills, the otherworldly beings whose stories keep the people of Ireland connected to their past.

Heininge, K. A. (2004). “Untiring Joys and Sorrows”: Yeats and the Sidhe. New Hibernia Review, 8(4), 101–116.

MacRitchie, D. (1893). Notes on the Word “Sidh.” The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, 3(4), 367–379.

MacRitchie, D. (1910). Druids and Mound-Dwellers. The Celtic Review, 6(23), 257–272.

Markey, A. (2006). The Discovery of Irish Folklore. New Hibernia Review, 10(4), 21–43.