No products in the cart.

November 29, 2025 3:14 pm

November 29, 2025 3:14 pm

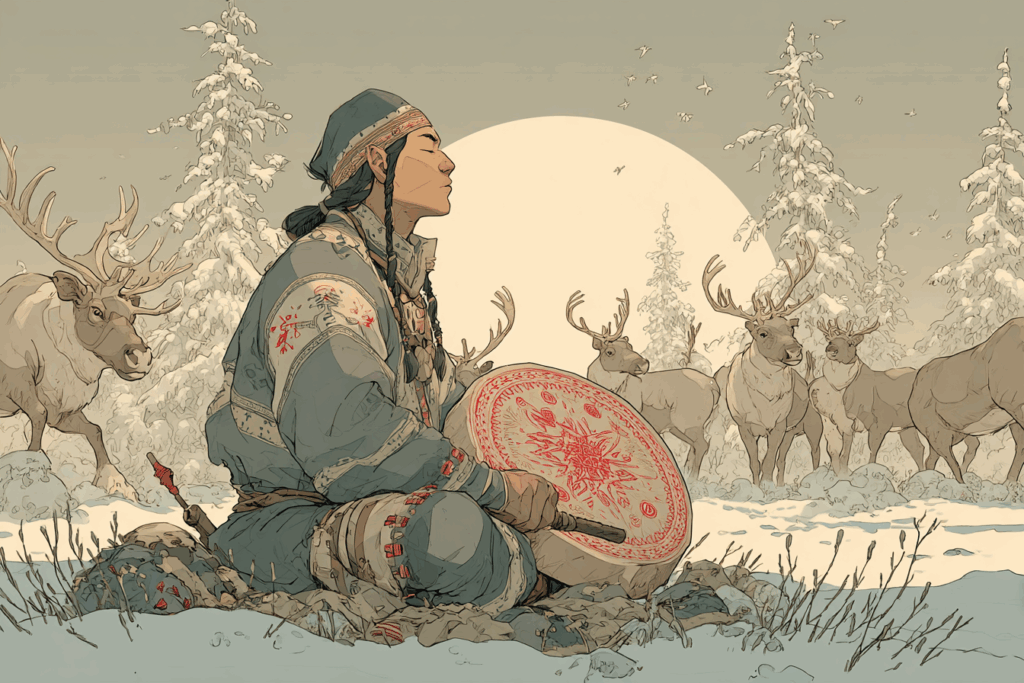

The shamanic drum, long central to Sámi tradition, was far more than a musical instrument.

This frame drum served as the heart of the noaidi’s craft.

The drum itself is a gateway between worlds, a divinatory tool, and a painted map of the cosmos.

In this post, we’ll uncover the fascinating history and spiritual importance of this handmade shaman drum.

We are exploring how its ceremonial use shaped Sámi life and how its voice, nearly silenced by colonial violence, is rising once again.

The Sámi shamanic drum which also known as a goavddis (depending on local region, terms can vary) is a sacred frame drum used by Sámi shamans (noaidis) in northern Scandinavia.

This handcraft was usually made from a bent wooden hoop, most commonly birch, fitted with reindeer hide or other animal hide stretched tightly to create a resonant drumhead (Kjellström, 1991, pp. 147–150).

The drum stick or beater was often carved from reindeer antler.

More than just a percussion instrument, this ceremonial drum was a spiritual tool used in healing, divination, and shamanic journeying.

The sound of the drum guided the noaidi through trance states.

Today, artisans replicate this sacred item in native-inspired styles, sometimes using elk hide, buffalo hide, or synthetic materials to capture its authentic sound.

Each handmade shaman drum frame drum was unique to its owner, reflecting the clan’s territory, cosmology, and spirit guides.

Most were oval-shaped, around 16 inches in diameter, though larger ceremonial drums could reach 20 inches or more.

The wooden frame which is usually birch or cedar wood was bound with sinew or lace to hold the hide in place (Kjellström, 1991, p. 149).

Painted symbols on the drumhead were typically drawn in red pigment, made from alder bark or other natural sources.

These motifs turned the drum into a cosmological diagram: gods, animals, celestial bodies, and sacred sites were all arranged across the stretched animal skin, creating a spiritual map (Pentikäinen, 2010, p. 4).

This made every shamanic drum a unique blend of artisan work and sacred text.

The drum is an important tool in Sámi spiritual life.

The shaman used it to induce trance states, during which he or she could journey across cosmic layers in order to heal, retrieve souls, or communicate with gods and spirits.

This sound healing technique involved steady beats from a drumstick or mallet, the rhythm echoing the wingbeats of spirit animals (Eliade, 1964, pp. 207–210; Hultkrantz, 1991, p. 36).

Through shamanic journeying, the noaidi traveled across the worlds symbolized on the drumhead from the underworld up to celestial spheres.

The drum’s authentic sound created sacred space and allowed the shaman to act as a mediator between people, animals, and deities (Pentikäinen, 1998, pp. 90–93).

One remarkable practice involved the drum’s use in divination.

During a session, the shaman would place a vuorbi which is a ring made of brass or horn on the drumhead and begin to beat around it.

The ring would bounce and slide across the hide frame hand drum, eventually settling on a specific symbol.

This movement was interpreted as the answer to a question: a lost reindeer’s location, the success of a hunt, or whether to perform a sacrifice (Schefferus, 1674, cited in Pentikäinen, 2010, p. 5).

Families would gather to witness the oracle at work, watching the bottom of the drum for the ring’s position.

The known drum became not just a musical instrument but a divine channel.

Such ceremonies involved both spirit music and practical concern, blurring the line between mystical and material.

The painted drumhead is a sacred text.

Northern Sámi drums were structured in layers: the upper part held celestial powers, the middle depicted human life, and the lower featured underworld spirits (Manker, 1938, p. 112).

In southern drums, the sun formed the center, from which human, animal, and divine figures radiated outward (Pentikäinen, 2010, p. 4).

Deities included Horagalles, the thunder god, often shown with his double hammer; Beaivi, the sun deity; and Radienattje, the high god (Wiklund, 1987, pp. 12–14).

The goat skin drum might also show animals like reindeer, fish, or bear all of whom are vital both as spiritual allies and as symbols of livelihood (Joy, 2015, p. 85).

Yes. In sound healing rituals, the noaidi used the drum to locate and retrieve lost souls of the sick.

These were known as soul-retrieval journeys.

Birds were especially important spirit guides in this work, capable of flying through all layers of the cosmos, from the underworld, midrealm, and the celestial spheres (Pulkkinen, 2005, p. 84).

Their presence on the drumhead echoed their importance in shamanic healing.

The deep tone of the elk or reindeer hide was said to mimic bird wingbeats.

In some Siberian and Tibetan traditions, similar sound patterns are found in journey drumming.

This is again reinforcing the universal value of the shaman drum across northern Eurasia (Eliade, 1964).

Christian missionaries viewed the drum as a threat.

In the 17th century, Sámi people across Norway, Sweden, and Finland were subject to forced conversions.

The shamanic drum was not simply just a percussion instrument but a tool of sorcery.(Rydving, 1995, p. 61, Higgins, 2022).

These events marked the end of drum-time, however, but not the end of Sámi identity.

Around 70 Sámi drums still exist, held in museums across Europe. The largest collection resides in the Nordiska Museet in Stockholm.

These drums are more than ethnographic artifacts. Indeed, they are sacred objects, comparable to bibles in their role as carriers of myth and ritual (Somby in Higgins, 2022).

In 2022, Poulsen’s drum was returned from Copenhagen to the Sámi Parliament, a rare act of cultural repatriation.

Today, Sámi artists and shamans are reclaiming their traditions by building new frame drums, reviving spiritual practices, and preserving the deep resonant sound that once guided their ancestors.

Contemporary handcraft revival includes making buffalo drums and goat skin drums inspired by Sámi forms.

Though some use synthetic materials like Fiberskyn or Remo Bahia for weather-resistance, many artisans prefer rawhide and natural finishes.

A handmade shaman drum frame drum round 16 or 22 inches in diameter is often favored for its authentic sound and spiritual resonance.

These drums are used in spiritual practice, drum circles, sound healing, and ceremonial settings.

Whether it’s a Remo Buffalo Drum or a cedar wood frame hoop with sinew-laced elk hide, the modern shamanic drum continues the ancient role of calling spirits, guiding journeys, and marking sacred space.

Eliade, M. (1964). Shamanism: Archaic techniques of ecstasy (Bollingen Series Vol. 76). Princeton University Press. (Original work published 1951)

Higgins, C. (2022, March 13). Three centuries on, a shaman’s precious rune drum returns home. The Guardian.

Hultkrantz, Å. (1991). The drum in shamanism: Some reflections. In T. Ahlbäck (Ed.), Sámi Religion (pp. 34–51). Åbo: Donner Institute.

Joy, F. (2015). Sámi shamanism, fishing magic and drum symbolism. Shaman: Journal of the International Society for Shamanistic Research, 23(1–2), 67–102.

Joy, F. (2020). The importance of the sun symbol in the restoration of Sámi spiritual traditions and healing practice. Religions, 11(6), 270.

Kjellström, R. (1991). The Saami shaman drum: Some reflections around variations in the drum pictures. In T. Ahlbäck (Ed.), Sámi Religion (pp. 146–163). Åbo: Donner Institute.

Manker, E. (1938). Die Lappische Zaubertrommel. Vol. I: Text. Stockholm: Thule.

Paulson, I. (1958). Comparative religion of the Lapps. Numen, 5(1), 53–75.

Pentikäinen, J. (1998). Shamanism and culture. Helsinki: Etnika.

Pentikäinen, J. (2010). The shamanic drum as cognitive map. Cahiers de Littérature Orale, 67–68, 1–12.

Pulkkinen, R. (2005). The Sámi shaman and their mythology. Helsinki: Finnish Literature Society.

Rydving, H. (1995). The end of drum-time: Religious change among the Lule Saami, 1670s–1740s. Uppsala: Almqvist & Wiksell.

Schefferus, J. (1674). Lapponia. Frankfurt: Christian Wolff.

Wiklund, K. B. (1987). Lapponica: Essays on Saami ethnography. Umeå: Centre for Arctic Studies.