No products in the cart.

November 24, 2025 2:12 pm

November 24, 2025 2:12 pm

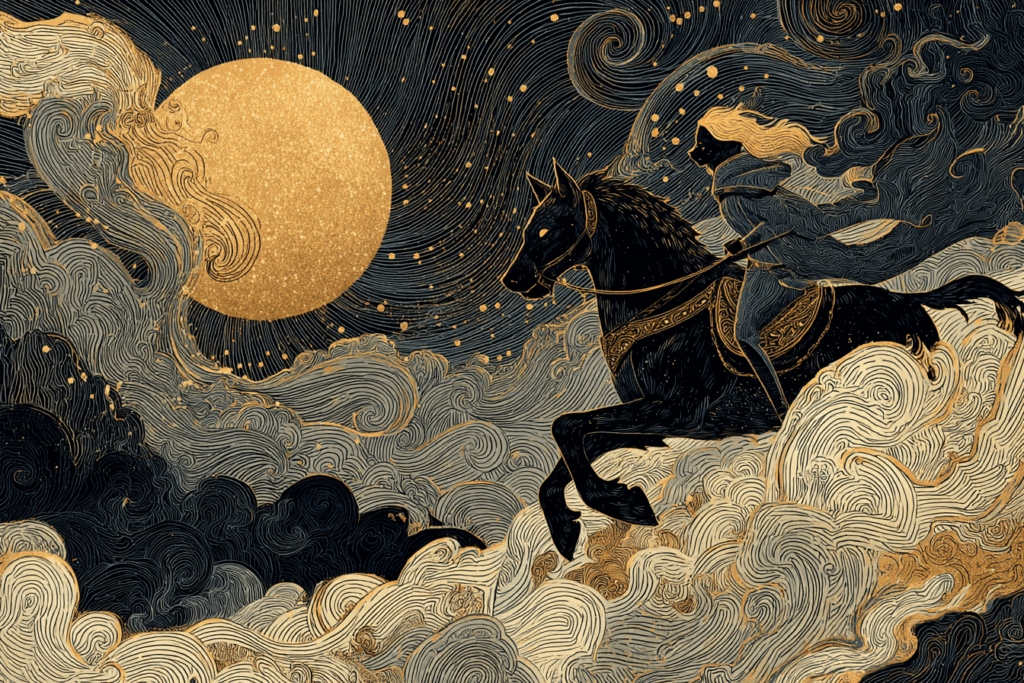

The moon in Norse mythology was not simply a glowing ornament drifting across the night sky.

He was a presence as a regulator of cosmic rhythm, a keeper of time, and a luminous being who shaped the order of the heavens.

When the sources speak of Máni, they portray far more than a distant heavenly body.

They describe a moon god with layered roles, mythic depth, and an identity rooted in both poetic imagination and astronomical observation.

This article offers a detailed look at Máni through Old Norse literature, comparative Indo-European material, and modern scholarship.

Readers interested in the Norse gods and goddesses, mythic cosmology, lunar symbolism, or the subtle architecture of Old Norse thought will find rich material here.

In Norse mythology, Máni appears as a quiet but powerful figure.

While sól, his radiant sister, represents sovereignty and daily rebirth.

Máni embodies measured rhythm, reflection, and the slow breathing of the cosmos.

Scholars note that the moon’s borrowed glow shaped how medieval Icelanders imagined this deity.

His light is luminous yet muted, an echo of the sun rather than its rival (Clunies Ross & Gade, 2012).

This duality shapes the mythic relationship between sól and máni.

She embodies heat, life, and unbroken motion; he moves through phases, expressing a cycle of presence, withdrawal, and return.

The sun and the moon form a complementary pair. Two celestial siblings bound by cosmic law and astronomical observation.

Máni becomes a personification of the moon who mirrors the human experience of insight.

The Old Norse lexicon preserves a complex lunar vocabulary.

The term tungl, originally meaning “heavenly body,” shifted over time until it referred specifically to the moon.

Linguist Sturtevant explains that the language appears intentionally balanced: máni parallels sól : sunna, forming matched pairs that reinforce cosmic symmetry (Sturtevant, 1954).

This linguistic pairing is not trivial.

It demonstrates how Norse speakers perceived harmony in the heavens: each celestial entity held two names.

One poetic and one functional, mirroring dual characteristics within the mythic cosmos.

Such structural symmetry reflects deeper cultural patterns.

The sun and moon themselves are siblings, the children of mundilfari in the mythic genealogies.

Their movement across the heavens forms a coordinated system that measures not only the day but the entire lunar year.

The Poetic Edda, especially the Alvíssmál, preserves a remarkable catalog of cosmic vocabulary.

Each supernatural race such as the gods, dwarfs, elves, giants names the sky and its celestial bodies differently.

Cohen’s analysis reveals that these multilayered names express the unique worldview of each mythic group (Cohen, 2020).

For example, the moon is called:

Each name reflects a different facet: identity, function, motion, illumination, or measurement.

The label “vanishing wheel” captures the waxing and waning cycle, a symbolic image connecting the moon to mortality. “

Counter of years” shows that the moon was central to calendrical reckoning, a role that ties Máni firmly to cosmic governance.

This varied terminology shows how deeply Norse mythology encoded observation into mythic narrative.

Every mythic being perceived the sky through its own nature, turning the heavens into a shared phenomenon.

Medieval Icelandic skalds blended Norse lore with classical and Christian cosmology.

Clunies Ross and Gade note that poets imagined the sky as sacred architecture.

The earth as a hall and máni as its lamp (2012). The moon’s borrowed glow thus becomes a metaphor for mediated knowledge, illumination without fire.

Such poetic images express a cultural understanding of the moon as a guide rather than a ruler.

While odin, thor, and other norse gods embody force or triumph, Máni embodies transition, steady rhythm, and reflective insight.

This reflective light shapes metaphors throughout Old Norse literature.

The moon’s glow is soft but penetrating, a quality that poets used to express wisdom, time, and the fragile beauty of night.

Sigurðsson’s ethnoastronomical work shows that Snorri’s mythic descriptions encode astronomical knowledge.

In Gylfaginning, snorri sturluson presents the gods placing the sun and moon in the sky to “count the years.”

This is not abstract metaphor. It describes the natural observation that the moon’s phases define months, seasons, and ritual calendars (Sigurðsson, 2014).

Other myths speak of the wolf Hati, or hati hróðvitnisson, who chases Máni.

This reflects the moon’s disappearance during its waning phase and its periodic darkening during a lunar eclipse.

The poetic wolf becomes a narrative version of astronomical events, as a way of embodying the sky’s motion in dramatic imagery.

Even in the nineteenth century, Icelanders used the mythic wolf-names to describe sundogs, showing how the cosmological vocabulary endured long after Christianity reshaped religious thought.

Knutson’s research on Viking Age burial goods reveals a worldview in which objects possessed agency.

Metals, amber, weapons, and stones participated in the relationships between the living and the dead (Knutson, 2023).

This animistic framework extended to celestial bodies as well.

The moon was not a passive disk; it was an ensouled presence within the cosmos.

In this worldview, máni becomes more than a mythological figure. He becomes a participant in a relational universe where light functions as a bridge between worlds.

His waxing and waning form a cosmic pulse, guiding seasons, rituals, and the movement between life and death.

This view helps explain why children Hjúki and Bil accompany Máni in the myths.

They personify the human side of lunar experience, the emotional and symbolic qualities that link people to celestial rhythms.

Germanic poetic language often associates magical decline with lunar imagery.

Harris observes that in Skírnismál, when Gerðr is cursed to fade “like the thistle,” the metaphor expresses cosmic contraction rather than simple botanical wilt (Harris, 1975).

Decline becomes cyclical, a temporary ebb before rebirth, mirrored in the moon’s retreat into shadow.

This connection between lunar rhythm and cosmic order adds depth to ragnarök motifs.

The waning of the moon parallels the waning of the world, and each small cycle echoes the larger eschatological one.

Máni’s monthly “death” is thus symbolic, a moment that opens the door to renewal.

His return expresses the Norse belief that balance is achieved through alternating dominance of light and darkness.

Sturtevant’s linguistic findings highlight the intentional symmetry in Old Norse naming conventions. Pairings such as:

form a linguistic architecture that mirrors celestial order (Sturtevant, 1954).

Cohen’s catalog of moon-names expands this pattern into a worldview where mythic beings reshape language according to their own natures.

Clunies Ross and Gade show how these names become poetic devices, while Sigurðsson traces their roots to naked-eye astronomical knowledge.

Together these patterns show that the Norse cosmos was articulated through language. Every term carried cosmological weight, turning myth into a system of ordered perception.

Indo-European moon deities share traits of measurement, transformation, and renewal.

The Vedic Soma, Iranian Mah, and Greek Selene all express similar functions of cyclic abundance and decline.

Cohen’s observation that one of Máni’s names, Mýlinn, resembles the Indo-European “world mill”.

This links the Norse moon to a broader Eurasian image of cosmic rotation (Cohen, 2020). The moon becomes part of a metaphysical machine turning the heavens.

These comparisons show that Máni’s role as god of the moon fits into a much older network of mythic ideas .

The ones that bind the lunar cycle to moral and cosmic regulation.

Sigurðsson describes the moment in Völuspá when the gods “set the moon to count the years” as a declaration of cosmic law.

Movement becomes authority. Observation becomes sacred order (Sigurðsson, 2014).

Knutson’s animism adds emotional depth: light itself participates in spiritual exchange.

Clunies Ross and Gade show how poets transform this observation into metaphor, giving Máni an intellectual and philosophical role. Harris links lunar imagery to ritual behavior.

Together these views reveal Máni as a figure who harmonizes sensory experience, language, and sacred rhythm.

Through him, Norse cosmology expresses a universe measured in cycles and not in linear progress.

Cohen, S. (2020). What do the gods call the sky? Naming the celestial in Old Norse. Culture and Cosmos, 24(1 & 2), 27–36. https://doi.org/10.46472/CC.1224.0205

Clunies Ross, M., & Gade, K. E. (2012). Cosmology and skaldic poetry. The Journal of English and Germanic Philology, 111(2), 199–207. https://doi.org/10.5406/jenglgermphil.111.2.0199

Harris, J. (1975). Cursing with the thistle: Skírnismál 31, 6–8, and OE metrical charm 9, 16–17. Neuphilologische Mitteilungen, 76(1), 26–33.

Knutson, S. A. (2023). Between the material and immaterial: Burial objects and their nonhuman agencies. In L. Gardeła, S. Bønding, & P. Pentz (Eds.), The Norse sorceress: Mind and materiality in the Viking world (pp. 83–93). Oxbow Books.

Sigurðsson, G. (2014). Snorri’s Edda: The sky described in mythological terms. In T. R. Tangherlini (Ed.), Nordic mythologies: Interpretations, intersections, and institutions (pp. 184–198). North Pinehurst Press.

Sturtevant, A. M. (1954). Concerning doublet synonyms in Old Norse. Modern Language Notes, 69(5), 321–324.