No products in the cart.

September 8, 2025 12:20 pm

September 8, 2025 12:20 pm

Celtic mythology is one of the richest bodies of myths and legends in the world, preserved in medieval manuscripts by Christian scribes who copied and reshaped earlier oral traditions of the Celts.

These tales range from the epic battles of the Tuatha Dé Danann and the Fomorians to tragic romances, voyages to the Otherworld, and the lore of gods and goddesses remembered across the Celtic nations.

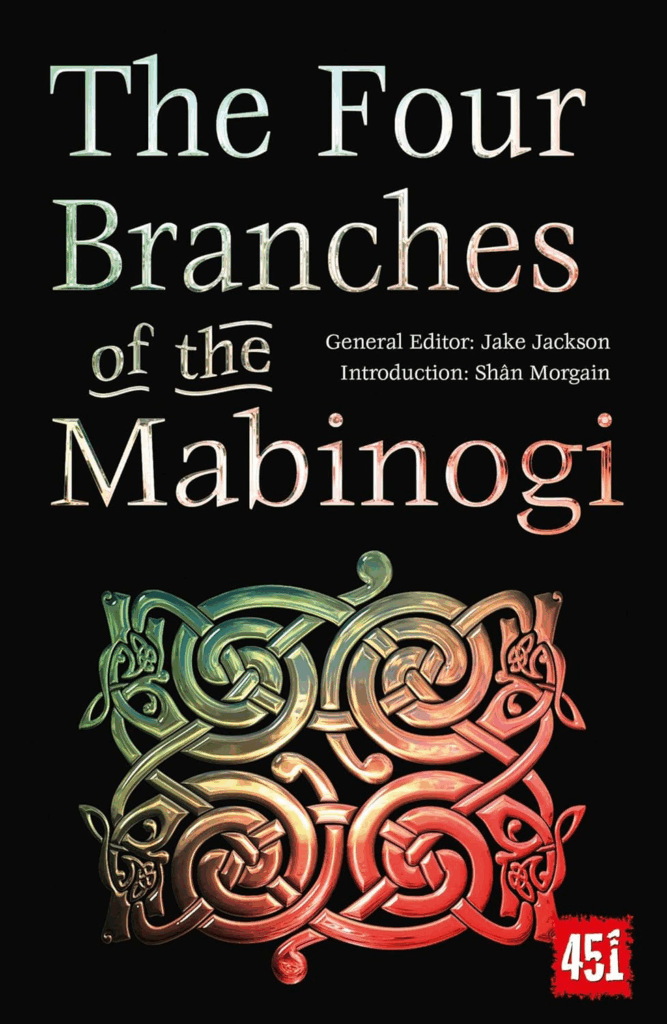

What survives in early Irish literature, Welsh tales like the Mabinogi, and even Arthurian legend allows us to glimpse how the Celtic peoples understood divinity, kingship, and the religious significance of their gods of Ireland, Gaul, and Britain.

In these narratives we see mythical heroes, tribal gods, the phantom queen Morrígan, the triple goddess Brigid, and the divine mother Danu alongside mortal kings such as Conaire Mór.

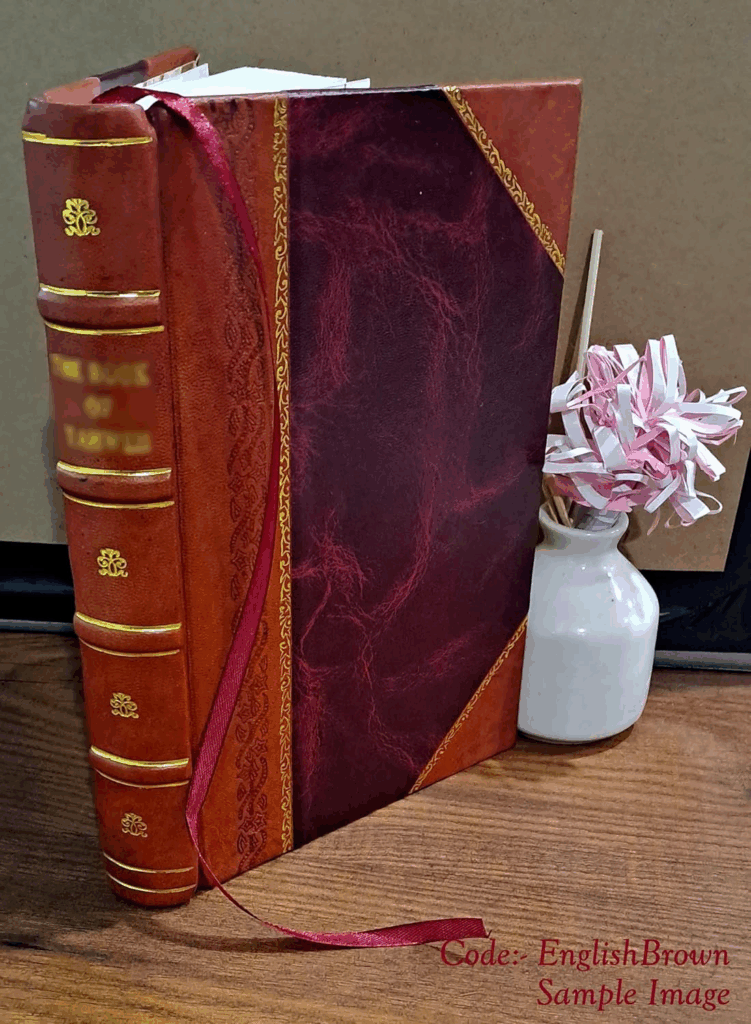

Much of this material was introduced to Celtic studies through the great compendia such as the Book of Invasions (Lebor Gabála Érenn) and the Book of Leinster.

Scholars like Proinsias Mac Cana and the editors of the Dictionary of Celtic Mythology have emphasized how ancient Celtic religion, with its many gods and polytheistic rites, connects with Proto-Indo-European patterns and archaeological evidence such as the Gundestrup Cauldron.

Yet these are not simply dry historical sources: they are living stories, still retold in live Irish dance, literature, and modern Celtic culture.

I earn a small commission for promoting these books on this blog. If there’s a particular book that interests you, please feel free to click on the title of the book in order to see more info.

Source: Lebor na hUidre (Book of the Dun Cow, c. 1100) and Book of Leinster (c. 1160).

The most famous Celtic legend of the Ulster Cycle, the Táin Bó Cúailnge (“Cattle Raid of Cooley”) recounts Queen Medb’s attempt to seize the great brown bull of Cooley.

Opposing her is the young hero Cú Chulainn, who defends Ulster in a series of single combats, including his duel with Fer Diad.

In Irish mythology this tale emphasizes honor, rivalry, and the tragic cost of war, while Christian monks carefully preserved it as part of early Irish literature.

Source: Yellow Book of Lecan (14th century) and fragments in Lebor na hUidre.

This Celtic myth of love and rebirth tells of Étaín, beloved by Midir of the Tuatha Dé Danann. Transformed and reborn, she eventually marries the mortal king Eochaid Airem, only to be reclaimed by her Otherworld lover after a contest of wits.

The tale reflects the mythological cycle’s fascination with reincarnation, divine-human unions, and the eternal pull between mortal and Otherworld realms.

Source: Recorded in later Irish manuscripts; part of the Three Sorrows of Storytelling.

Aoife, jealous stepmother of the children of Lir, transforms them into swans condemned to wander Irish waters for nine hundred years. They endure storms on Lake Derravaragh, the Sea of Moyle, and the Atlantic until Christian monks baptize them, releasing them from enchantment. This Celtic legend highlights the transition from pagan magic to Christian faith and survives as one of the best-loved Irish myths.

Source: Book of Leinster (c. 1160).

One of the Three Sorrows of Storytelling in Irish mythology, this narrative tells of Deirdre, prophesied to bring ruin to Ulster. She elopes with Naoise, but King Conchobar lures them back and treacherously slays him and his brothers. Deirdre, consumed with grief, dies soon after. The tale foreshadows the Táin Bó Cúailnge and exemplifies Celtic tales of doomed love and prophecy.

Source: Survives in a 12th-century recension.

In this branch of Celtic mythology, the Tuatha Dé Danann fight the Fomorians for sovereignty of Ireland. The god Lugh Lámhfhada slays Balor of the Evil Eye by casting a sling-stone through his destructive gaze. The Morrígan, phantom queen of battle, proclaims victory, while Nuada of the Silver Hand and the gods of Ireland secure renewal for the land. The myth preserves echoes of Proto-Indo-European storm-god battles and shows how the Tuatha Dé Danann embody the gods and heroes of the Celtic world.

Source: Book of Leinster (c. 1160).

Conaire Mór, High King of the Gaels, is doomed when he violates a web of gessa (taboos). Trapped in the burning hostel of Da Derga, he dies alongside his champions. This Celtic tale reads like an apocalypse in miniature, where even a chief god–ordained king cannot escape fate once the druids’ laws are broken.

Source: Lebor na hUidre (c. 1100).

Bran mac Febal sails across the sea with companions, encountering islands of delight and marvels until he reaches the Land of Women. When he returns, centuries have passed in Ireland. His tale belongs to the Otherworld voyage genre of Celtic mythology, a reminder that mortal time collapses before divine eternity.

Source: Recorded in 17th-century manuscripts; oral roots in the Fenian Cycle.

Gráinne elopes with the young warrior Diarmuid, fleeing the aging hero Fionn mac Cumhaill. After years of pursuit and reprieve, Diarmuid dies from the goring of a magical boar, while Fionn refuses to save him. This Celtic legend of the Fianna stresses loyalty, jealousy, and tragic destiny within Gaelic heroic tradition.

Source: Survives in medieval ballads and prose.

The bard Oisín is taken by Niamh of the Golden Hair to the Land of Youth. After centuries of joy, he returns to find the Fianna gone and ages instantly when he touches Irish soil. He narrates the glory of the Celtic gods and heroes to Saint Patrick, embodying the shift from ancient Celtic religion to Christian Ireland.

Source: First Branch of the Mabinogi, White Book of Rhydderch (c. 1350).

Pwyll exchanges places with Arawn, king of Annwn, for a year and defeats Hafgan in single combat. He later wins the mysterious Rhiannon, who embodies sovereignty and the divine mother archetype. This Welsh story illustrates the bonds between human rulers and the Otherworld, and it stands as a branch of Celtic mythology that foregrounds just rule.

Source: Second Branch of the Mabinogi.

Married to the Irish king Matholwch, Branwen is abused, and her brother Brân the Blessed leads a disastrous war. A magical cauldron revives the dead until Efnisien destroys it at the cost of his life. Branwen dies of heartbreak, and only seven survivors return. The tale is both Irish mythology and Welsh tragedy, stressing the ruinous effects of insult and violence.

Source: Third Branch of the Mabinogi.

Manawydan, with Rhiannon and Pryderi, endures an enchantment that leaves Dyfed barren. By capturing a mouse that is truly the wife of his enemy, he compels the lifting of the spell. This Celtic myth privileges patience and wisdom over warfare, aligning Manawydan with tribal gods of negotiation rather than force.

Source: Fourth Branch of the Mabinogi.

King Math’s nephews betray him, and he punishes them with animal transformations. The boy Lleu Llaw Gyffes is born under Arianrhod’s curses but is armed and named through Gwydion’s trickery. His flower-wife Blodeuwedd betrays him and is turned into an owl. Themes of metamorphosis, the triple goddess, and sovereignty pervade this Welsh branch of Celtic mythology.

Source: Mabinogi corpus, White and Red Books (14th century).

Culhwch, cursed to wed only Olwen, must perform impossible tasks set by her giant father Ysbaddaden. With Arthur and his companions he hunts the boar Twrch Trwyth and completes the quests. The giant is slain, and Culhwch weds Olwen. This Arthurian legend links Celtic myth with heroic catalogues of gods and heroes.

Source: Mabinogion, medieval Welsh redactions.

The Roman emperor Magnus Maximus dreams of Elen, a maiden in Wales, and finds her in Caernarfon. She becomes Elen of the Ways, remembered for building roads. The tale elevates the Celts by connecting them with imperial Rome, blending British mythology and historical sources with a myth of sovereignty.

Source: Peniarth MS 2 (16th century).

Gwion Bach accidentally tastes three drops from Ceridwen’s cauldron of inspiration and becomes the bard Taliesin after a chase of transformations. His gift of awen (inspiration) recalls the religious significance of druids and the bard as chief god-inspired figure in Celtic culture. The story combines supernatural powers with the divinity of poetry.

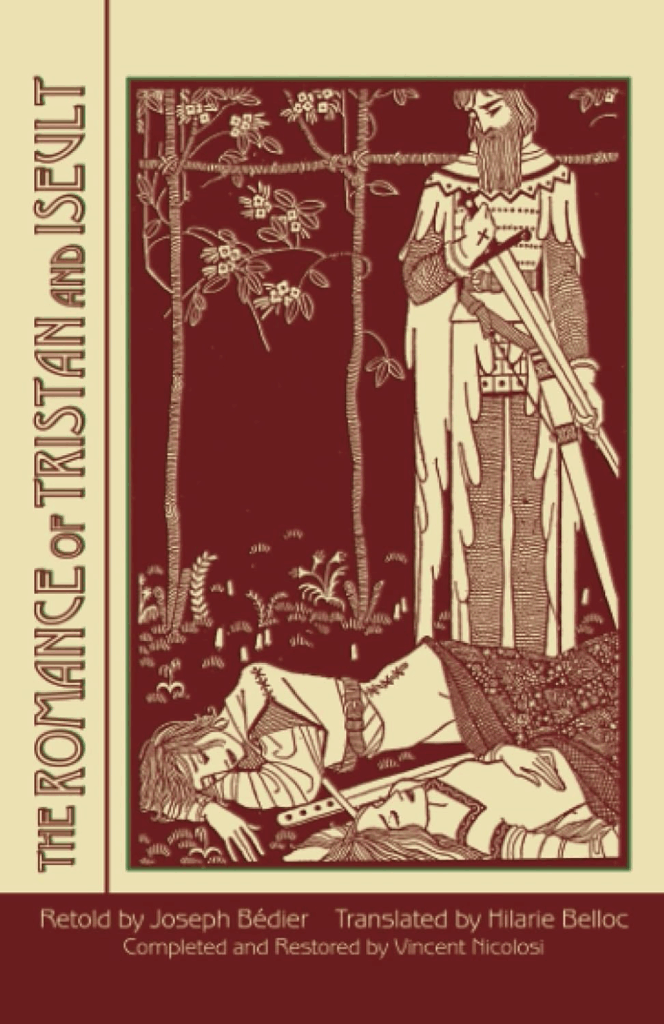

Source: Breton and Cornish tradition, first written in 12th-century French verse.

Tristan escorts Iseult to marry King Mark but drinks a love potion with her. Their doomed affair ends with their deaths, their grave sprouting an entwined vine and briar. This Celtic legend influenced the Arthurian cycle and dramatizes the tension between fate, loyalty, and desire.

Source: Breton legend; Albert Le Grand, Vie des Saints de la Bretagne Armorique (1636).

King Gradlon’s magnificent city is destroyed when his daughter Dahut opens the sea-gates, often at the urging of a devilish lover. The ocean swallows Ys, and Dahut becomes a morgen (mermaid). The myth reflects ancient Celtic religion’s storm gods such as Taranis, the danger of hubris, and the contest between pagan and Christian divinity.

Source: Irish myth and Manx folklore, remembered in the Manannan Ballad (16th century).

Manannán, chief god of the sea, cloaks the island in mist to protect it. The Gaels paid him tribute of rushes at midsummer. Associated with the Tuatha Dé Danann, he wields supernatural powers, a magic horse, and the crane-bag of treasures. Even after Christianity, he remained guardian of the Celtic world’s island people.

Source: Scottish Gaelic oral tradition; collected in Alexander Carmichael’s Carmina Gadelica (1899).

The Cailleach, also called Beira, personifies winter’s harshness. She hurls boulders to shape the land, freezes the soil with her hammer, and rules until Beltane, when she turns to stone, reawakening at Samhain. She is a Celtic myth of the divine mother as landscape-shaper, a polytheistic survival of ancient Celtic religion, remembered in seasonal rites.