No products in the cart.

November 3, 2025 2:19 pm

November 3, 2025 2:19 pm

Throughout Irish and Celtic mythology, few figures embody the stark beauty of winter as completely as the Cailleach, the veiled goddess of winter known in Gaelic tradition as the Hag of Beara.

Her story spans mountains, glens, and coasts, shaping how generations understood the frozen season as both harsh and sacred.

This exploration of her myth and legend uncovers how she became Ireland and Scotland’s Queen of Winter, a divine hag whose storms, stones, and sea-spray still echo across the land.

The article below brings together early folklore scholarship and modern Celtic studies to illuminate how the Cailleach evolved from ancient earth deity to folk weather-maker and why her power endures every time frost covers the hills.

The Cailleach is a Celtic goddess whose name in Old Irish simply means “veiled woman” (Hutton, 2022, p. 149). She appears as an ancient hag ruling the winter months, a personification of winter itself.

In Irish folklore, she is the aged counterpart to Brigid, the youthful spring goddess, together forming a dual cycle of decay and renewal (Hull, 1927, p. 230).

Scholars describe her as the divine hag who strikes the ground with her staff to summon frost and whose breath freezes the soil (Hutton, 2022, pp. 145–147).

The Cailleach is associated with storms and winter winds, embodying the elements that preserve the earth’s life in dormancy until spring’s return.

Folklorist Donald Alexander McKay documented Highland stories describing the Cailleach Bheur, “the blue old woman of the hills,” who gathers her firewood before Imbolc.

If 1 February is bright and sunny, the Cailleach gathers her firewood to prolong the frost; if the weather on 1 February is poor, she cannot leave her glen, and the rest of the winter will be mild (McKay, 1932, pp. 153–155).

This folklore links directly to agricultural timekeeping. Her ability to command foul weather made her both feared and honored, a sovereignty goddess ruling nature’s balance between scarcity and survival.

Each year, as winter and death gave way to spring, her reign ended in a final storm and the end of winter and her fading power as the land thawed.

In Scotland and Ireland, the Cailleach is guardian of the deer, the bodach of the wild herds who depend on her mercy. McKay (1932, p. 150) describes her driving her herd across the glens as snow begins to fall.

This Celtic myth portrays her as mother of the forest animals and as keeper of sovereignty over the natural world.

Many tales say that the Cailleach created the mountains across the land by dropping stones from her apron.

These acts of creation of the landscape mark her as a primordial deity, blending geology and mythology.

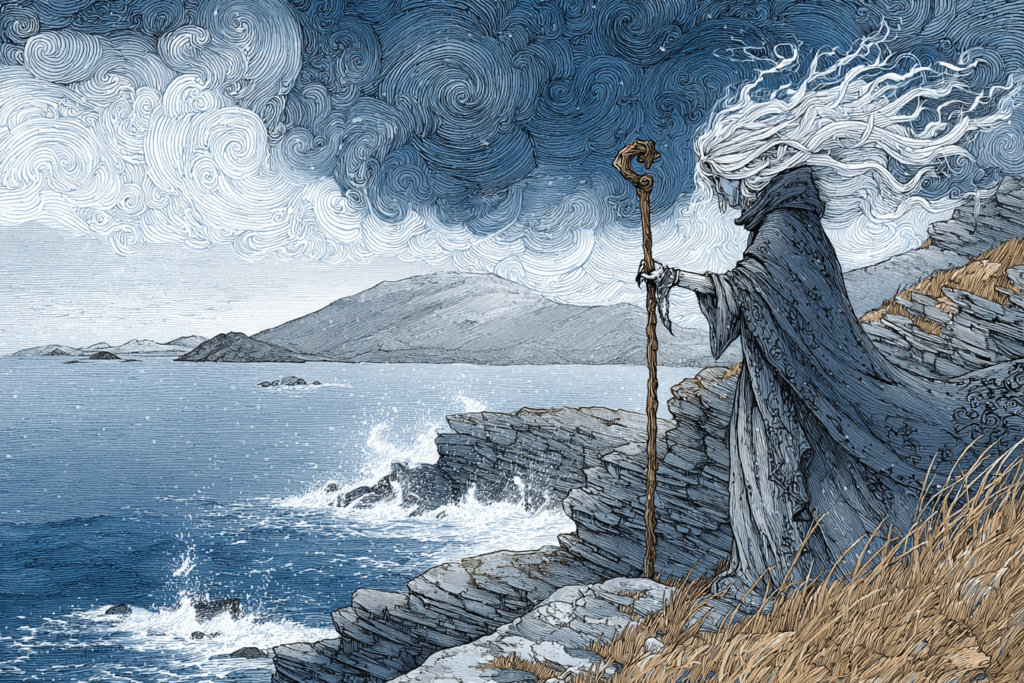

The Beara Peninsula in Cork still bears her name, Cailleach Bhéara, the old woman of Beara whose stone form gazes out to sea.

Early texts such as the Book of the Cailleach (a scholarly term used for her oral corpus) preserve fragments of her legend.

Hull (1927, p. 225) traces her to pre-Christian cosmology, calling her “a personification of the earth in its wintry aspect.”

Hutton (2022, pp. 155–157) explains that the Cailleach became central to folklore through centuries of retelling, transforming from a prehistoric nature deity into a moral symbol of aging, wisdom, and the cycle of time.

Her mythic evolution demonstrates how Irish folklore adapted pagan archetypes into Christian storytelling.

Some later poems even portray her as the Nun of Beara, an ascetic old woman lamenting lost youth yet still commanding the storms and winter of the Atlantic coast.

The Cailleach and her family appear in Celtic mythology from Ireland to the Isle of Man.

One version tells of Caillagh ny Groamach, the sullen weather-woman who predicts the season’s length by gathering sticks (Hutton, 2022, p. 147).

In Glen Lyon of Perthshire, stories speak of her stone household at Tigh nam Bodach, where clay figures representing the Cailleach, her bodach, and their children are tended annually to maintain good weather (Hutton, 2022, p. 147).

Such rituals illustrate how the Cailleach is associated with household protection and sovereignty over the elements, revealing her dual role as domestic guardian and cosmic weather-maker throughout Scotland and Ireland.

Sharon Paice MacLeod’s research situates the Cailleach’s myth within Celtic deities tied to sacred water.

Wells, whirlpools, and waterfalls symbolized otherworld wisdom and transformation (MacLeod, 2006, 2007, pp. 338–343).

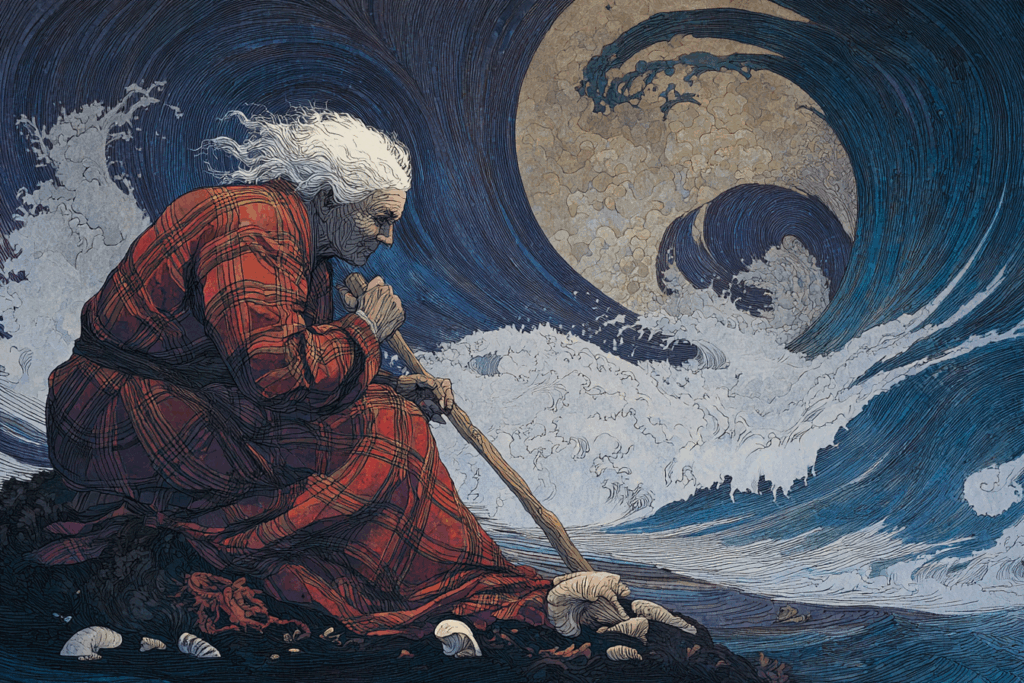

The story of her winter by washing her plaid in the Corryvreckan whirlpool unites storm, sea, and renewal.

When she spreads her cloak to dry, the land turns white with snow (Hull, 1927, pp. 234–236).

This act represents purification through chaos. The whirlpool becomes her well of youth, echoing myths of Manannán Mac Lir, the sea god linked to rebirth.

The image affirms the Cailleach’s dominion over both creation and transformation, sustaining the world through elemental power.

Though often feared, the Cailleach is fundamentally a mother goddess, the aged counterpart of goddess Brìghde, who embodies light and fire.

Their seasonal opposition mirrors the beginning of winter and the revival at Imbolc, when warmth returns to the soil.

The two goddesses represent life’s polarity, each dependent on the other for the world’s renewal.

In many Gaelic hymns, the Cailleach’s surrender at Imbolc allows Brìghde to reawaken fertility, a transform of divine power rather than defeat.

The old hag who freezes the fields becomes the midwife of rebirth, fulfilling her role as Queen of Winter and cyclical sustainer of time.

Across Celtic myth, physical landscapes preserve her story. Peaks like Slieve na Calliagh in Meath and Ben Cruachanin Argyll are said to have been shaped by her.

At the Cliffs of Moher, local legend calls her the Witch of Ben, watching the horizon for her lost love, Mac Lir.

These sites root the figure of the Cailleach in tangible earth and sea, mapping her presence across Ireland and Scotland.

In Glen Cailleach, villagers once left offerings at midsummer to ensure gentle weather.

Such traditions show how the Cailleach appears as both destructive and protective, embodying the sovereignty of nature itself.

L. M. C. Weston’s analysis of Old English charms reveals how the hag archetype symbolized female ritual authority.

The Cailleach, likewise, is a veiled woman whose hidden face conceals the mystery of creation.

Her veil represents not shame but cosmic knowledge, a marker of the sacred feminine that wields both birth and decay.

Weston (1995, p. 286) associates such figures with the powerful women who presided over life-giving rites.

In this context, the Cailleach embodies enduring wisdom, transforming fear of age into reverence for continuity and a theme central to Celtic folklore and mythology alike.

Every cycle, the Cailleach transforms the world through her seasonal acts. She raises tempests, sculpts the snow, and finally yields to warmth at the end of winter.

According to Highland tradition, she drinks from a well of youth each century to regain vigor, echoing the rebirth of the sun after solstice (Hutton, 2022, pp. 144–145).

Her reign as Queen of Winter lasts from Samhain to Imbolc, when she relinquishes power to Brigid. This ritualized shift defines 1 February as a moment of balance.

When February is bright and sunny, the Cailleach would continue her rule; when rain or snow confines her, spring begins.

Such tales preserve agricultural wisdom and cosmic rhythm entwined in one mythic narrative.

Modern scholarship sees the Cailleach as more than relic or superstition. She is a Celtic goddess whose myths explain the eternal cycle of destruction and renewal.

Her lore from Glen Lyon to Beara Peninsula continues to inspire poets, pagans, and folklorists.

Hutton (2022, p. 158) concludes that the Cailleach may not be a single ancient deity but a synthesis of regional spirits and weather hags.

Yet she remains a living myth as well as an expression of humanity’s respect for the winter season and the endurance of the land.

The means the Cailleach embodies is timeless: that even in frost, life is preparing to return.

Hull, E. (1927). Legends and traditions of the Cailleach Bhéara or Old Woman (Hag) of Beara. Folklore, 38(3), 225–254. Taylor & Francis, Ltd. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1256390

McKay, J. G. (1932). The deer-cult and the deer-goddess cult of the ancient Caledonians. Folklore, 43(2), 144–174. Taylor & Francis, Ltd. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1256538

MacLeod, S. P. (2006/2007). A confluence of wisdom: The symbolism of wells, whirlpools, waterfalls and rivers in early Celtic sources. Proceedings of the Harvard Celtic Colloquium, 26/27, 337–355. Department of Celtic Languages & Literatures, Harvard University. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40732065

Hutton, R. (2022). The Cailleach. In Queens of the Wild: Pagan Goddesses in Christian Europe – An Investigation (pp. 143–158). Yale University Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv2jn91rr.10

Weston, L. M. C. (1995). Women’s medicine, women’s magic: The Old English metrical childbirth charms. Modern Philology, 92(3), 279–293. The University of Chicago Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/438781

MacNeill, M. (1965). Irish folklore as a source for research. Journal of the Folklore Institute, 2(3), 340–354. Indiana University Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3814154