No products in the cart.

November 6, 2025 3:17 pm

November 6, 2025 3:17 pm

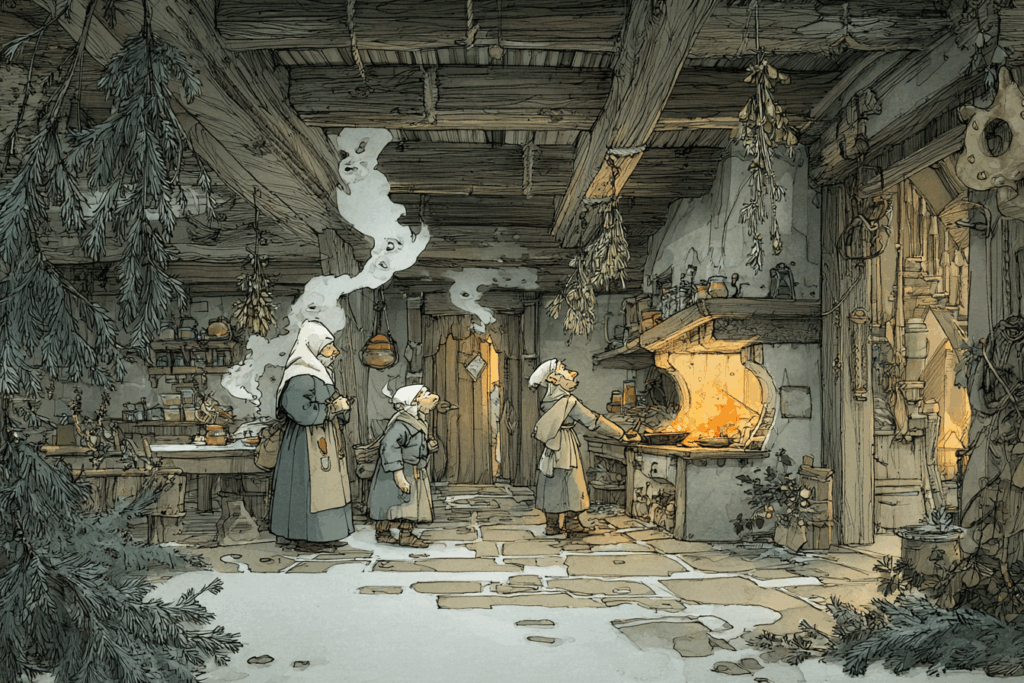

Winter was historically the time of closed windows, stagnant air, sickness, and long nights when spirits were believed to wander.

Burning herbs and incense was both practical and magical. In rural Europe, juniper branches, pine resin, birch bark, and mugwort were tossed onto embers to cleanse stale air and protect the household.

Long before modern incense sticks, families understood that fragrant smoke changed how a place felt. Indeed, transforming the environment, lifting mood, signaling blessing, and marking sacred time.

Nair’s work on aromatics explains that humans discovered the beneficial effects of burning herbs and resins in prehistory and soon adopted incense into ritual life across cultures (Nair, 2013, p. 5).

Long before Europe’s winter smoke rituals, traditional incense was cultivated across the Near East, Arabia, Persia, and India.

Frankincense, myrrh, storax, and other resinous materials became sacred offerings in temples, for healing, and to mark holy time.

Maritime and land trade routes carried resin westward, spreading the idea that scented smoke bridged the visible and invisible world.

As Reinarz notes, incense was central to ancient devotion, offering a sensory link between human and divine through fragrant air (Reinarz, 2014, pp. 65–67).

These early blends were made from natural materials, not synthetic fragrance oils.

By the classical period, ports in the Mediterranean were receiving precious resins.

Families used them not only in temples, but during winter feasts, purification rites, and household rituals.

Scented smoke symbolized vitality and protection when illness and cold threatened survival.

Nair observes that incense burning became popular in personal homes because even small amounts of resin or a tiny cone could transform the atmosphere of a room (Nair, 2013, p. 7).

A single pinch on embers filled a house with fragrance, marking winter nights as special.

Long before imported resins became common, European villages practiced winter fumigation for health, blessing, and protection.

Birch bark symbolized new beginnings. Rowan wood guarded the home. Juniper was known for cleansing. Folk households walked burning branches through rooms to drive out sickness and ill-luck.

These customs match what sensory historians describe as a “boundary ritual”, the moment when a space becomes protected or sacred through scent(Reinarz, 2014, pp. 68–70).

Most rural families used natural incense from local woods and herbs rather than exotic blends.

Evergreen resin carried the symbol of life that never died, an idea especially powerful in the dead of winter.

Mugwort was said to frighten off illness and unseen forces. As Nair explains, humans respond strongly to aromatic compounds, and even tiny amounts could shift the emotional feeling of a room (Nair, 2013, p. 7).

Rural families did not choke their houses in smoke; they burned small pinches, enough to bless the air and mark the night. This approach lives on today in quality incense made with natural ingredients rather than synthetic oils.

Though grown far away, frankincense and myrrh incense became part of winter ritual across Europe.

They were mixed with local herbs to make seasonal blends. Their aroma was deeper, resinous, and symbolic of healing and protection.

Reinarz notes that pleasant fragrance was historically linked with blessing, wellbeing, and divine favor, whereas foul air suggested danger or corruption (Reinarz, 2014, p. 66).

In winter, when air felt heavy and illness common, fragrant smoke promised comfort. Today, a small incense stick or resin cone of frankincense and myrrh can still create that same soothing scent.

Midwinter was an important and indeed mythical season when people believed the line between worlds grew thin.

The simple act of smoldering herbs on a coal pan was a household ritual: rooms, cupboards, rafters, beds, animals, and tools were touched by scented air.

Baum’s research shows that in many German-speaking regions, smoke ceremonies were performed during the dark nights between the old year and the new as a form of protection and boundary-making (Baum, 2013, pp. 332–334).

Even without imported resins, pine sap or juniper on embers carried the same meaning: blessing, cleansing, and renewal through fragrant smoke.

Across Alpine regions, the Rauhnächte (or “smoke nights”) between late December and early January were devoted to cleansing the home.

Families walked through rooms with burning juniper or resin to chase away misfortune.

Baum notes that while official church ritual discouraged incense after the Reformation, rural households maintained winter fumigation as part of seasonal folk religion (Baum, 2013, p. 339).

Smoke became a private ritual rather than a public one. Knowledge passed quietly through families.

Winter incense traditions are not limited to Europe. Variations appear across the Near East, North Africa, Central Asia, and parts of India, where aromatic wood, resin, or herbs are burned for good fortune and healing during cold months.

Reinarz argues that the link between scent, wellbeing, and sacred action predates written history (Reinarz, 2014, pp. 65–66).

Whether in a European farmhouse or a desert caravan, the idea is the same: a little smoke turns an ordinary night into a blessed one.

Traditional winter incense is not sugary or perfumed. It is resinous, herbal, and evergreen. Common ingredients include:

These ingredients echo the old winter blends—protective, cleansing, earthy, and warm.

Some modern artisanal incense makers produce minimalist, hand-rolled blends or incense cones made with high-quality plant powders.

Others sell sampler sets or even an incense of the month club featuring seasonal scents. Whether a Japanese stick with a bamboo core, a resin chunk, or a small cone, the effect is the same: quiet comfort in the dark of winter.

Burn small amounts, allow fresh air afterward, and let the smoke mingle with candlelight and winter air.

A single piece of resin, stick, or burner-safe cone is enough to transform a space.

Nair suggests that adequate ventilation makes incense safer and more enjoyable (Nair, 2013, pp. 7–8).

Winter was never about filling a room with thick smoke; it was about small, meaningful fragrance that changed the feeling of a home.

Baum, J. M. (2013). From incense to idolatry: The reformation of olfaction in late medieval German ritual. The Sixteenth Century Journal, 44(2), 323–344.

Nair, U. (2013). Incense: Ritual, health effects and prudence. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, 23(1), 5–9.

Reinarz, J. (2014). Heavenly scents: Religion and smell. In Past Scents: Historical perspectives on smell (pp. 65–83). University of Illinois Press.