No products in the cart.

August 6, 2025 11:37 am

August 6, 2025 11:37 am

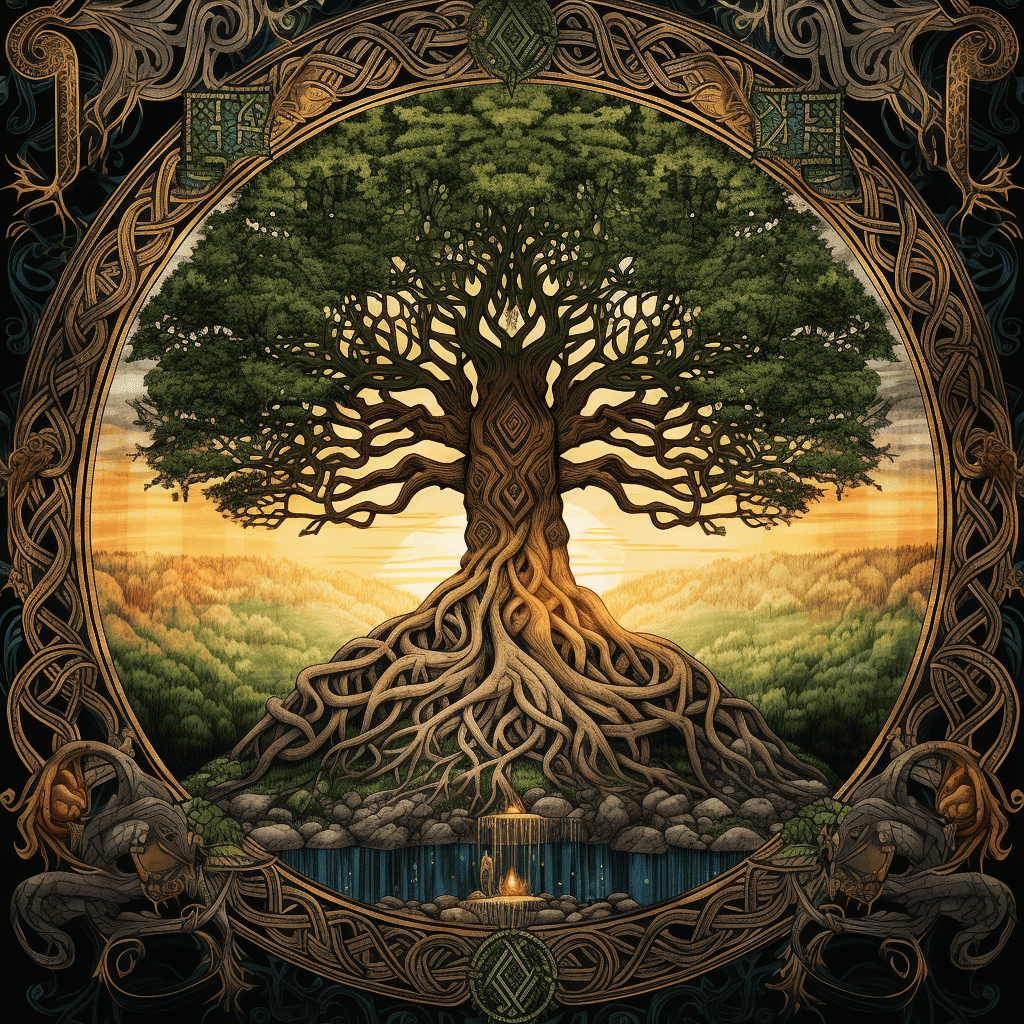

At the heart of Norse cosmology stands Yggdrasil, the mighty world tree. It is not simply a backdrop for Norse mythology; it structures the Norse cosmos itself.

According to von Schnurbein (2003), the vertical orientation of Yggdrasil reflects a shamanic model of the universe, connecting upper, middle, and underworld realms.

This cosmological framework, shared by various northern Eurasian traditions, supports the existence of the nine realms of Norse mythology, known as the nine worlds.

The name Yggdrasill itself has sparked intense scholarly discussion.

One common interpretation holds that it means “Odin’s horse,” referring to the myth where Odin hangs himself on the tree to gain knowledge of the runes (Lindow, 2002).

This is not a mere poetic image; it establishes Yggdrasil as the axis of sacrifice, wisdom, and transformation, and places it at the center of Norse religion.

The nine realms, also referred to as the nine worlds of Norse mythology, are not made of formless chaos. They are distinctly structured and represent the connected nature of the cosmos.

Hilda Ellis Davidson (1975) suggests these realms are grouped in triads: Asgard and Vanaheim for the gods, Alfheim for the light elves, Midgard for humankind (the human world), Jotunheim for giants, Svartalfheim or Nidavellir for dwarves, Niflheim and Helheim for the dead, and Muspelheim for fire giants.

These distinct worlds are described as being suspended within and around Yggdrasil.

As Lindow (2002) notes, this tree is not just metaphorical; it is a literal, towering structure upon which the realms in the Norse mythic system are arranged.

Each realm in Norse tradition holds its own significance.

Yggdrasil is a living ash tree with immense spiritual function.

It supports, connects, and suffers. It has three primary roots: one extending to the realm of the Aesir, one to the world of the giants in Jotunheim, and one into Niflheim, the realm of the dead.

Near the roots of Yggdrasil, the Norns dwell at Urd’s well, weaving the fate of the gods and mortals.

Yet the tree is not untouched. Yggdrasil is assaulted by threats from every direction.

A serpent named Nidhogg gnaws at its roots; four deer feed on its branches; and there are serpents within its trunk (Lindow, 2002).

The forces in Norse mythology are not always in harmony. This tree constantly balances chaos and order.

Von Schnurbein (2003) argues that Yggdrasil’s vertical design mirrors ritual shamanism in old Norse culture.

Among shamanic traditions, the tree Yggdrasil reflects the vertical world axis.

The trunk represents the mortal world, the crown touches the heavens (home of the Aesir gods in Asgard), and the roots stretch to the underworld (Helheim, Niflheim).

In this structure, Odin’s hanging from Yggdrasil becomes a shamanic initiation.

According to Norse myth, he sacrifices himself to himself. This ordeal mirrors shamanic journeys observed in various parts of the world, and the tree serves as a map for cosmological vision and divine access.

The name Yggdrasill remains layered and obscure.

Sivert Hagen (1903) interprets it as a kenning: “Yggr’s steed,” meaning Odin’s horse, referring to Yggdrasil as a gallows.

In Norse sagas, this connects directly to the creation of the world through suffering and knowledge.

Hagen also explores other possibilities. Perhaps Yggdrasil was once imagined as a mountain or some kind of cosmic pillar.

Could the phrase have signified something beyond Odin’s execution site?

While debate continues, most scholars agree that this tree was understood by early Scandinavians as the central axis of the nine realms in Norse mythology.

The nine realms are not neutral spaces.

They express spiritual and moral hierarchies.

According to Davidson (1975), Asgard, the home of the Aesir, is a realm of divine order, home to Valhalla and the gods of Norse myth.

Midgard, the world of humans, is where choices, loyalties, and battles unfold.

Below these, primordial forces stir in Niflheim, Helheim, and Muspelheim—the realm of fire and chaos.

These realms in Norse mythology also express fate.

When Surtr, the fire giant, rises from Muspelheim, it signals the end of the world.

The realm of fire and heat described by some as one that would consume the world is not just mythic scenery but an active force of change.

Both Davidson (1975) and von Schnurbein (2003) stress that Yggdrasil is more than narrative. It forms part of a ritual worldview.

Parallels with Norse creation stories, Siberian traditions, and Norse texts suggest the tree reflects deep Eurasian memory.

These stories hint that even as Asgard and Midgard fall, Yggdrasil endures.

The rainbow bridge, Bifröst, connects Midgard to Asgard, allowing the Norse gods to move between worlds.

Each of the nine realms, along with Yggdrasil, functions not only mythically but ritually.

Their continued presence in Norse culture suggests the lasting power of symbolic geography.

Here’s a brief orientation to the nine realms in Norse tradition:

These two realms of death such as Helheim and Niflheim stand in contrast to Asgard and Vanaheim, forming mirrored cosmological opposites.

All nine realms of Norse cosmology are held within the structure of Yggdrasil.

Davidson, H. E. (1975). Gods and Myths of Northern Europe. Penguin Books.

Hagen, S. N. (1903). The origin and meaning of the name Yggdrasill. Modern Philology, 1(1), 57–69. https://www.jstor.org/stable/432424

Lindow, J. (2002). Norse Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Heroes, Rituals, and Beliefs. Oxford University Press.

von Schnurbein, S. (2003). Shamanism in the Old Norse Tradition: A theory between ideological camps. History of Religions, 43(2), 127–145.